@FiloInglesaUZ Retropost, 2011. De vocal a presidenta. Ascendiendo. https://t.co/IJNAehwtXb

— JoséAngelGarcíaLanda (@JoseAngelGLanda) November 30, 2021

—oOo—

La mejor manera de ocultar algo es ponerlo a la vista de todos.#repentinitis pic.twitter.com/8ERTkh7Kme

— REPENTINITIS (@Repentinitis2) November 30, 2021

No se sabe la causa..... pic.twitter.com/v3PRdX8lFM

— 🇪🇸DaniWolf🏛️#YoNoVoto🇪🇦 (@DaniWolv) December 7, 2021

Les dejo por acá el final de la película italiana Omicron (1964). Los comentarios sobran. pic.twitter.com/X2wjJT5m7r

— Federico Leicht (@LeichtFederico) November 29, 2021

Donde se me cita:

Hancock, Mark (U of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue W., Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada; mark.hancock@uwaterloo.ca), Rebecca Langer, Amberly H. West, and Neil Randall. "Applications as Stories." Challenges for implementing gamification for behavior change: lessons learned from designing Blues Buddies CHI workshop 2013. 2 May 2013.*

http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7201/2/7201_4383-vol2.PDF

2013

_____. "Applications as Stories." In Challenges for implementing gamification for behavior change: lessons learned from designing Blues Buddies CHI workshop 2013. 44-49. Online at Academia.*

https://www.academia.edu/5184373/

2021

—oOo—

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Screenplay by Steph Lady and Frank Darabont, based on Mary Shelley's novel.

Prod. Francis Ford Coppola, James V. Hart, John Veitch. Coprod. Kenneth Branagh, David Parfitt. Prod. design Tim Harvey. Photog. dir. Robert Pratt. Ed. Andrew Marcus. Costumes by James Acheson. Music: Patrick Doyle.

Cast: Robert de Niro, Kenneth Branagh, Hom Hulce, Helena Bonham Carter, Aidan Quinn, Ian Holm, Richard Briers, John Cleese. Cherie Lunghi, Treuyn McDowell.

TriStar Pictures / Japan Satellite Broadcasting / The Indie Prod. Company / American Zoetrope, 1994.

_____. "French History." From A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. Online at Multi Language Documents. 2017.*

2022

_____. "French History." From A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. Online at Mexico Documents 15 March 2018.*

2021

_____. "French History." De A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. Online at CUPDF 15 mayo 2018.*

2021

_____. "French History." From A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. Online at United States Documents 15 March 2018.*

2023

____. "French History / Mi bibliografía de historia de Francia." From A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. In García Landa, Vanity Fea 29 Nov. 2021.*

https://vanityfea.blogspot.com/2021/11/mi-bibliografia-de-historia-de-francia.html

2021

—oOo—

Aquí insertamos "Readers and Reading", de A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology.

Es otra bibliografía temática procedente de mi Bibliografía de Teoría Literaria, Crítica y Filología, que aparece a trozos en un sitio mexicano, de estos que no sé si los llame repositorios o recopilatorios de textos. Además los retranscribe, como si hiciera falta (a mí ninguna), pero bueno, me gusta que les dé un formato insertable. Este listado va sobre lectores y lectura—literarios, se entiende. Sobre lo que es leer letras y palabras y oraciones hay un listado aparte.

El mismo listado aparece en versión insertable aquí:

_____. "Readers & Reading." From A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. Cupdf 7 March 2018.*

2022

—oOo—

_____. "Scientific Texts." From A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. Online at Mexico Documents 27 May 2017.*

2021

_____. "Scientific Texts." From A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. Online at Vdocuments 27 May 2018.*

2019

_____. "Scientific Texts." From A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology. In García Landa, Vanity Fea 29 Nov. 2021.*

https://vanityfea.blogspot.com/2021/11/scientific-texts.html

2021

_____. "Scientific Texts." Online at PDFslide.*

2023

From A History of American Literature, by Richard Gray. (The American Century, pp. 590-94).

"Ours is the century of unreason," Eudora Welty declared once, "the stamp of our behavior is violence and isolation: nonmeaning is looked upon with some solemnity." Flannery O'Connor (1925-1964) would have agreed with some of this, but not all. What troubled her was not lack of reason but absence of faith. "The two circumstances that have given character to my writing," O'Connor admitted in her collection of essays, Mystery and Manners (1969), "have been those of being Southern and being Catholic"; and it was the mixture of these two, in the crucible of her own eccentric personality, that helped produce the strangely intoxicating atmosphere of her work—at once brutal and farcical, like somebody else's bad dream. A devout if highly unorthodox Roman Catholic in a predominantly Protestant region, O'Connor interpreted experience according to her own reading of Christian eschatology — a reading that was, on her admission, tough, uncompromising, and without any of "the hazy compassion" that "excuses all human weakness" on the ground that "human weakness is human." "For me," she declared, "the meaning of life is centered in our Redemption by Christ"; and to this she might well have added that she neither saw humankind as worthy of being redeemed, nor Redemption itself as anything other than a painful act of divorce from this world. With rare exceptions, the world she explores in her work—in her novels Wise Blood (1952) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960) and her stories gathered in A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955) and Everything that Rises Must Converge (1965) — is one of corrosion and decay. It is a world invested with evil, apparently forsaken by God and saved only in the last analysis by His incalculable grace. It is a netherworld, in fact, a place of nightmare, comic because absurd, and (as in early Christian allegory) the one path by which its inhabitants can travel beyond it is that of renunciation, penance, and extreme suffering.

O'Connor herself was inclined to talk in a distinctly equivocal way about the relationship between the two circumstances that shaped her life, her region and her faith. Sometimes, she suggested, it was her "contact with mystery" that saved her from being stereotypically Southern and "just doing badly what has already been done to completion." In the Bible Belt, after all, Roman Catholics wre and still are in a distinct, occasionally distrusted minority. Other times, she argud that there was a perfect confluence, or at least congruity. "To know oneself," she said once, "is to know one's region." And her region, in particular, enaled her to know herself as a Catholic writer precisely because it was "a good place for Catholic literature." It had, she pointed out, "a sacramental view of life": belief there could "still be made believable and in relation to a large part of society"; and, "The Bible being generally known and revered in the section," it provided the writer with "that broad mythical base to refer to what he needs to extend his meaning in depth." Whatever the truth here—and it probably has to do with a creative tension between her education in Southern manners and her absorption in Catholic mystery — there is no doubt that, out of this potent mixture, O'Connor produced a fictional world the significance of which lied precisely in it apparent aberrations, its Gothic deviance from the norm. Her South is in many ways the same one other writers have been interested in — a wasteland, savage and empty, full of decaying towns and villages crisscrossed by endless tobacco roads. And, like Twain, she borrows from the Southwestern humorists, showing a bizarre comic inventiveness in describing it. Her characters — the protagonist Haze Motes in Wise Blood, for instance — are not so much human beings as grotesque parodies of humanity. As O'Connor herself has suggested, they are "literal in the same sense that a child's drawing is literal": people seen with an untamed and alien eye. Where she parts company with most other writers, however, is in what she intends by all this, and in the subtle changes wrought in her work by this difference of intention.

O'Connor herself explained that difference by saying that "the novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant to him." His or her audience, though, will find those distortions "natural." So such a novelist has to make his or her vision "apparent by shock." "To the hard of hearing you shout," she says, "and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures." Her figures are grotesque, in other words, because she wants us to see them as spiritual primitives. In order to describe to us a society that is unnatural by her own Christian standards — and to make us feel its unnaturalness — she creates a fictional world that is unnatural by almost any accepted standards at all. O'Connor's characters are distorted in some way, social or physical, mental or material, because their distortions are intended to mirror their guilt, original sin, and the spiritual poverty of the times and places they inhabit. That is only half the story, though. From close-up, these characters may seem stubbornly foolish and perverse, ignorant witnesses to the power of evil. But ultimately against their will, they reveal the workings of eternal redemption as well. They are the children of God, O'Connor believes, as well as the children of Adam; and through their lives shines dimly the possibility that they may, after all, be saved. So an extra twist of irony is added to everything that happens in O'Connor's stories. Absurd as her people are, their absurdity serves as much as it does anything else, as a measure of God's mercy in caring for them. Corrupt and violent as their behavior may be, its very corruption can act as a proof, a way of suggesting the scope of His extraordinary forgiveness and love. As, for instance, O'Connor shows us Haze Motes preaching "the Church without Christ" and declaring "Nothing matters but that Jesus was a liar," she practices a comedy of savage paradox. Motes, after all, relies on belief for the power of his blasphemy: Christ-haunted, he perversely admits the sway over him of the very faith he struggles to deny. Every incident in Wise Blood, and all O'Connor's fiction, acquires a double edge because it reminds us, at one and the same time, that man is worthless and yet the favoured of God — negligible but the instrument of Divine Will. The irremediable wickedness of humanity and the undeniable grace of God are opposites that meet head on in her writing, and it is in the humor, finally, that they find their issue, or appropriate point of release. What we are offered on the surface is a broken world, the truth of a fractured picture. But the finely edged character of O'Connor's approach offers an "act of seeing" (to use her own phrase) that goes beyond that surface: turning what would otherwise be a comedy of the absurd into the laughter of the saints.

A writer whose fictional world wa as strange yet instantly recognizable as O'Connor''s was Carson McCullers (1917-1967). "I have my own reality," McCullers said once toward the end of her life, "of language and voices and foliage." And it was this reality, her ghostly private world that she tried to reproduce in her stories (collected in The Mortgaged Heart (1971)), her novella The Ballad of the Sad Café (1951), and her four novels: The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter (1940), Reflections in a Golden Eye (1941), The Member of the Wedding (1946), and Clock without Hands (1961). She gave it many names, over the years, and placed it consstently in the South. Southern though its geographical location might be, however, it was like no South ever seen before. It was another country altogether, created out of all that the author had found haunting, soft, and lonely in her childhood surroundings in Georgia. It was also evolved out of her own experience of melancholy, isolation, and occasional if often illusory happiness. "Everything that happens in my fiction has happened to me," she confessed in her unfinished autobiography (Illumination and Night Glare (2000)). Her life, she believed, was composed of "illumination," moments of miraculous insight, and "night glare," long periods of dejection, depression, frustration—feelings of enclosure within herslf. So are the lives of her characters. The people she writes about may seem or feel strange or freakish because of their anomalous desires, aberrant behavior, or grotesque appearance. But in their freakishness they chart the coordinates of all our lives; their strangeness simply brings to the surface the secret sense of strangeness all of us share in what McCullers sometimes called our "lonesomeness." So, for example, The Ballad of the Sad Café revolves around a dance macabre of frustrated love, thwarted communication "There are the lover and the beloved," the narrator tells us, "but these two come from different countries." Similarly, The Member of the Wedding is an initiation novel in which the lonely, sensitive, 12-yar-old protagonist, Frankie Adams, is initiated into the simple ineradicable fact of human isolation: the perception that she can, finally, be "a member of nothing." At the heart of McCullers's work lies the perception Frankie comes to, just as the protagonist of Clock Without Hands, J. J. Malone does when he learns that he has a few months to live. Each of us, as Malone feels it, is "surrounded by a zone of loneliness"; each of us lives and dies unaccompanied by anyone else; which is why, when we contemplate McCullers's awkward and aberrant characters, we exchange what she called "a little glance of grief and lonely recognition."

Whereas McCullers published only four novels in her short life, and O'Connor only two, Joyce Carol Oates (1938-) has produced more than fifty. In addition, she has written hundreds of shorter works, including short stories and critical and cultural essays, and several of her plays have been produced off Broadway. Often classified as a realist writer, she is certainly a social critic concerned in partiular with the violence of contemporary American culture. But she is equally drawn toward the Gothic, and toward testing the limits of classical myth, popular tales and fairy stories, and established literary conventions Many of her novels are set in Eden Country, based on the area of New York State where she was born. And in her early fiction, With Shuddering Fall (1964) and A Garden of Earthly Delights (1967) she focuses her attention on rural America with its migrants, social strays, ragged prophets, and automobile wrecking yards. In Expensive People (1968), by contrast she moved to a satirical meditation on suburbia; and in Them (1969) she explored the often brutal lives of the urban poor. Other, later fiction, has shown a continued willingness to experiment with subject and forms. Wonderland (1971), a novel about the gaps between generations, is structured around the stories of Lewis Carroll. Childwold (1976) is a lyrical portrait of the artist as a young woman. Unholy Loves (1979), Solstice (1985), and Maya: A Life (1986) cast a cold eye on the American professional classes. You Must Remember This (1987) commemorates the conspiratorial obsessions of the 1950s; Because it is Bitter, and Because it is My Heart (1991) dramatizes the explosive nature of American race relations. Blonde (2000) is an imaginative rewriting of the life of the movie icon Marilyn Monroe, while My Sister, My Love (2008) reimagines an actual murder case, focusing on how ambitious parents alternately push and ignore their unhappy children. Her fiction is richly various in form and focus; common to most of it, however, including recent works like Missing Mom (2005) and The Gravedigger's Daughter (2007), is a preoccupation with crisis. She shows people at risk: apparently ordinary characters whose lives are vulnerable to threats from society or their inner selves or, more likely, both. In Oates's much anthologized short story "Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?" (1970), for instance, the central character, Connie, is an all-American girl, fatally at ease with the blandness of her adolescent life. She becomes the helpless victim of a caller, realistically presented yet somehow demonic, whom she mistakes for a friend. Her sense of security, it is intimated, is a dangerous illusion. The stories and novels of Oates are full of such characters. Some, like Connie, find violence erupting from their surroundings; others, frustrated by the barren or grotesque nature of their lives and social circumstances, erupt into violence themselves. With all of them, there is the sense that they are the victims of forces beyond their control or comprehension. Whatever many of them may believe to the contrary, they are dwellers in a dark and destructive element.

Why We Tell Stories: The Science of Narrative

—oOo—

#MIRONEWS Muere la escritora Almudena Grandes. Solo 61 años ¿cuantas víctimas vamos a soportar sin abrir los ojos? ¿Otra casualidad? Descanse en Paz. Un aullido pic.twitter.com/dCu9oz6XVh

— FERNANDO LÓPEZ-MIRONES (@FLMIRONES) November 27, 2021

#MIRONEWS “Tenía cancer” caso resuelto. A ver, “cáncer” tenemos casi todos, se curan el 70% y se puede vivir con uno o varios 40 años. No sean ignorantes. Gente con esta patología controlada desde hace años fallece justo AHORA tras inocularse. No el año pasado, AHORA

— FERNANDO LÓPEZ-MIRONES (@FLMIRONES) November 27, 2021

#MIRONEWS Cómo se miente con protocolos; en España se considera “NO VACUNADO” a todo paciente con una dosis o pautacompletas de menos de 14 días. Así todos los muertos recién inoculados pasan por “no vacunados” cuando en realidad fallecieron por repentinitis. Un aullido

— FERNANDO LÓPEZ-MIRONES (@FLMIRONES) November 27, 2021

Nos ha dejado Almudena Grandes. Escritora brillante y mujer comprometida. Un abrazo a su familia y amigas. Eskerrik asko por tu literatura, por tu compromiso y por tu solidaridad. pic.twitter.com/BBoeORMFBg

— Arnaldo Otegi 🔻 (@ArnaldoOtegi) November 27, 2021

—oOo—

🤪Más de 150.000 personas en la manifestación convocada por #Jusapol contra la reforma de la #LeyDeSeguridadCiudadana.#NoALaInseguridadCiudadana#27NMadrid

— jusapol (@jusapol) November 27, 2021

💪🇪🇸@jucilnacional @JupolNacional pic.twitter.com/lqI1viA6kx

‼️ #URGENTE

— G.P. de VOX en Cataluña (@VOX_Cataluna) November 26, 2021

Mensaje de @Igarrigavaz denunciando el 'apartheid sanitario' creado por el separatismo:

"Plantaremos batalla donde haga falta, y animamos al conjunto de los ciudadanos a reivindicar sus derechos y libertades". pic.twitter.com/v2Lx0UFC38

@FacultadFiloZgz La OMS sobre las mascarillas - https://t.co/2Kk2BitwrO

— JoséAngelGarcíaLanda (@JoseAngelGLanda) November 26, 2021

Una vez más quiero dejar mi protesta por la obligatoriedad que tenemos los profesores de impartir las clases con mascarilla, tanto las personas que están felices con ella como los que la llevamos muy a disgusto y aguantando su molestia permanente. La ley en sí es abusiva y estúpida, más digna de Afganistán que de España (y ahí lo dejo, que si no no acabo)—pero deja margen a que no use la mascarilla quien tenga dificultades respiratorias con ella. SIN DICTAR MÁS REQUISITOS AL RESPECTO.

Pero a continuación viene la Universidad, y el reglamento, que aplica esa ley de modo abusivo, obligando a presentar un certificado médico de un neumólogo que acredite que se sufren enfermedades que hacen imposible el uso de la mascarilla. Este paso y este requisito añadido es UN ABUSO. A mi entender y en mi libre opinión, que ya está en duda en este país si podemos opinar libremente sobre estas cuestiones.

En fin, que el ABUSO ADMINISTRATIVO se ve redondeado cuando se aplica selectivamente la norma, y se obliga al uso continuado de la mascarilla excepto en los casos en que el Rectorado o las autoridades o la Unidad de Prevención deciden hacer la vista gorda, o no usar mascarilla ellos mismos. Sin requerirse al parecer un certificado médico (el que yo les presenté en cambio no les valía, y me abrieron un expediente sancionador), e instruyéndonos sobre la obligatoriedad de seguir estas normas A LA VEZ QUE ELLOS LAS IGNORAN (ver por ejemplo minuto 44.44, o continuadamente en estas Jornadas organizadas por Prevención de Riesgos Laborales).

Esto es (por parte del Rectorado y sus aplicadores de Protocolos) no sólo incoherente, sino también PREPOTENTE Y ABUSIVO. Es un atropello a la libertad de las personas mucho más allá de lo que dictan las necesidades de aplicar una ley ya de por sí más que cuestionable. A mí se me acusaba de grave atentado a la salud pública al no aceptarse mi certificado médico, ni que usase pantalla facial, y me amenazaban con suspensión de empleo y sueldo durante AÑOS. Finalmente quedó el expediente, afortunadamente y con mejor criterio, en una amonestación por parte del Rectorado.

PUES YO TAMBIÉN LES AMONESTO, SEÑORES. NO ABUSEN, NO CONTRIBUYAN A POTENCIAR EL ALARMISMO, Y NO SE NOS RÍAN EN LA CARA.

Respuesta de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales ante las pandemias

—oOo—

—oOo—

Bragg, Melvyn, et al. "The Scriblerus Club." BBC4 (In Our Time) 9 June 2005.*

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p003k9cm

2014

_____. "Pope." BBC4 (In Our Time) 9 Nov. 2006.*

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0038x97

2021

A lecture on Pope's Essay on Criticism:

Nada más ver este gráfico, se sacan indicaciones claras sobre si hay que vacunarse o no. La respuesta es, por supuesto, QUE NO. https://t.co/CnTVtdn4oN

— JoséAngelGarcíaLanda (@JoseAngelGLanda) November 25, 2021

Me citan (nos citan) en una tesis de Stuttgart sobre el tema:

Arnold, Annika. (Göttingen). "Narratives of Climate Change: Outline of a Systematic Approach to Narrative Analysis in Cultural Sociology." Ph.D. diss. U of Stuttgart, 2015. Online at Academia.*

https://www.academia.edu/26753872/

2021

_____

Ahora se mete a opinar sobre el cambio climático hasta la Inteligencia Artficial:

Grok 3 Beta, et al. "A Critical Reassessment of the Anthropogenic CO2-Global Warming Hypothesis: Empirical Evidence Contradicts IPCC Models and Solar Forcing Assumptions." Science of Climate Change 5.1 (2025): 1-16.

https://x.com/ChGefaell/status/1903775488075501669/photo/1

2025

—oOo—

Un articulo de Paul Craig Roberts denunciando la Plandemia:

The

extraordinary measures we are witnessing in Austria and Europe and the

news report that Australia is moving covid patients and contacts into

quarantine camps comprise proof that the covid measures are unrelated to

public health. https://twitter.com/

Both HCQ and Ivermectin are known Covid cures and preventatives. The

evidence is overwhelming. In India’s largest province, Uttar Pradesh,

with a dense population three times larger than the combined population

of Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, covid was contained by the use of

Ivermectin. https://

In no country has covid vaccination had success, much less success like Ivermectin in India.

Fake “fact check” sites funded by Big Pharma have tried to bury the news of India’s success with Ivermectin by covering it up with disinformation in order to protect Big Pharma profits.

In Uttar Pradesh, Ivermectin was used as a preventative as well as a cure. A pill a week keeps the virus away. Moreover, it is thoroughly established that covid’s mortality is essentially limited to people with serious illnesses who are not treated with HCQ or Ivermectin when they catch Covid, but are left to get well on their own and when they don’t are killed in hospitals with ventilators or remdesivir, two proven highly unsuccessful “treatments.”

The Austrian lockdown makes no sense for a variety of reasons. The most obvious is that Austria’s lockdown does not apply to people who go to work. So a large percentage of Austrians will be free to move about. What is the point of allowing people to go to work but not to a restaurant? It is too silly for words and must have some other purpose.

In Law, Legislation, and Liberty, Friedrich A. Hayek wrote that emergencies are the pretexts that governments use to erode civil liberties and that the erosions remain after the emergency passes or the pretend emergency is exposed. In the past 20 years we have seen the demise of civil liberty because of the “war on terror” and now again on the basis of a faked “Covid pandemic.” President George W. Bush used 9/11, an obvious false flag attack, to set aside the Constitutional protection of habeas corpus and detain people indefinitely without presentation of evidence to a court. President Obama used the fake war on terror to execute citizens on suspicion alone without due process of law. Now people are losing their jobs, businesses, and freedom based on an occasionally lethal virus, the prevention and cure of which is blocked by Big Pharma and Big Medicine’s Covid protocol.

When the Soviet Union collapsed and China abandoned communism, people expected a reign of freedom to result. Instead, the Western World has seen an assault on civil liberty that is reminiscent of life under Stalin and Mao. In America today and throughout the so-called “free West” people are punished for exercising First Amendment rights. The Constitution and human rights laws do not protect them. Journalist Julian Assange has been held in violation of Anglo-American habeas corpus for a decade, and no court has done anything about it. There are no protests from law schools, bar associations, or journalists. An obvious conclusion is that the members of institutions designed to support civil liberty no longer believe in civil liberty.

As the belief in freedom has weakened in the West, unless we join together and revive it by refusing to accept lockdowns and “vaccine” mandates, we won’t much longer be free.

—oOo—

Comentario que pongo:

Si el futuro es ahora, el futuro muestra cosas poco prometedoras también, como la intolerancia y el regreso de la censura, muy prominente hoy en el periodismo y en las redes, cuando hace bien poco era "cosa de Franco". Hoy se acepta y se defiende. Sin ir más lejos, la propia Facultad de Filosofía y Letras acaba de cerrar la posibilidad de poner contribuciones o comentarios en su página de Facebook, que de moderadamente multivocal se ha vuelto unidireccional y meramente institucional. Una red social donde sólo habla el Administrador no merece tal nombre. Enmiéndese por favor esta deriva tan perniciosa, habilitando un espacio donde pueda haber conversación y opinión en el ámbito de la Facultad.

—oOo—

Esto lo pongo en un par de rincones que se han olvidado de cerrar a los comentarios. Pero está claro que las opiniones no son bienvenidas, las disidentes (¿de quién?) por supuesto, pero ni tan siquiera las favorables o consonantes. Hale a cerrar el chiringuito hasta que escampe y se acabe el virus. El mental, digo.

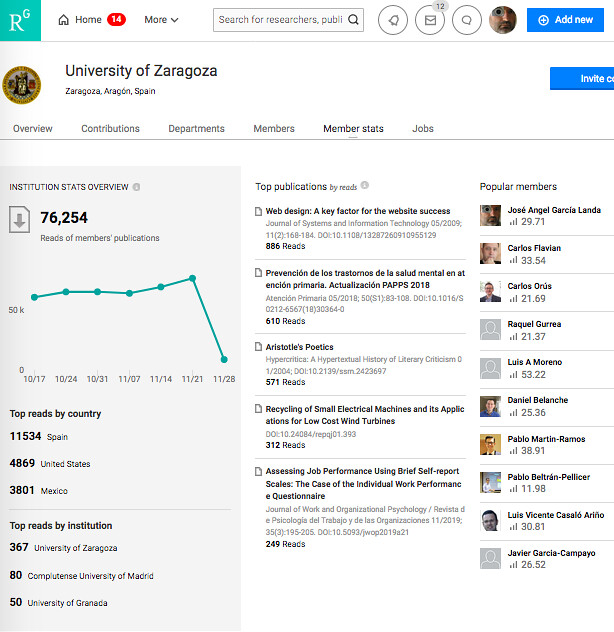

Para poner todo esto un poco más en contexto, quizá no sobre aclarar que semana sí semana también, desde hace años, soy el profesor más leído de mi universidad—al menos según los repositorios.

Igual da. Aquí vale más la consigna que radian las mentes más simples —"¡negacionista! negacionista!"—que la reflexión propia, el pensamiento, el debate o la conversación abierta.

Esta plaga moral de intolerancia y prepotencia, esta afición franquista (por utilizar un término comprensible en nuestro entorno) a la censura y a impedir la libertad de opinión, no es sin embargo privativa de nuestra Facultad. Ésta se mueve con el signo de los tiempos, y mucho me temo que me ha censurado por poner opiniones ofensivas al Covidismo o Tragacionismo ambiental. Cosas por ejemplo contra las Vacunas, que son el sacramento de esta nueva religión que nos ha invadido, al igual que las Mascarillas son su shibboleth impuesto por la fuerza.

Les avisé, en efecto, a mis colegas de la facultad, de que no continuaran con sus pautas de vacunaciones pues en Reino Unido la mortandad entre vacunados es el doble que entre no vacunados. Una cosa que podría uno pensar que les afecta y va en favor del interés público. Y si estoy equivocado (en su opinión) bien me podrían decir "Estimado compañero: gracias por tu información y por tu preocupación por nuestra salud; ahora bien, queremos señalar que los datos que nos pasas tienen otras lecturas por tal y cual, o no son fiables por tal y cual, etc., y nosotros por nuestra parte animamos a la gente a vacunarse por el bien público etc. etc." Eso es una conversación académica, informada (si aportan datos) y educada.

Esto es todo lo contrario. Esto es histeria azuzada, cierre de filas conformista, despotismo, tragacionismo,

En AEDEAN se ha producido el mismo fenómeno. En lugar de decir: "Estimado socio y compañero, esta página es temática y borraremos todas las publicaciones que no estén relacionadas directamente con los estudios ingleses y norteamericanos, con los literarios queremos decir, no con asuntos políticos o sociológicos de ningún tipo en estos tiempos de pandemia y desinformación" (etc.).

(Esa opción ya sería discutible, de hecho, más que discutible...)

Pero no. Prefieren ante la duda cargarse el espacio de diálogo para todo el mundo. Yo esta gente no sé realmente cómo le funciona la cabeza, o qué criterio les asoma al mirarse al espejo.

Y mientras en periódicos y radios y televisores ya se airean sin el menor pudor las nociones más nazis que imaginarse puedan acerca de qué hacer con los no vacunados, o con los negacionistas, cómo confinarlos, perseguirlos, o inocularlos a la fuerza por el Bien Común. Que son sin duda gente infectada, muy enferma de actitud, y que deben ser apartados de la sociedad según procedimientos bien acreditados por la Historia, y estudiados con horror y aspavientos de escándalo por todo este patético personal académico.

_____________________

P.S. Continúa la conversación de arriba, con el administrador de la página de Filosofía y Letras.

___________

PS: El nuevo blog de AEDEAN:

https://twitter.com/search?q=%40aedeaninfo&src=typed_query&f=live

Y el nuevo blog de la Facultad:

https://twitter.com/search?q=%40FacultadFiloZgz&src=typed_query&f=live

—oOo—

Por desgracia, les he salido negacionista y políticamente incorrecto. Lo mismo pasa en Ibercampus, que se han puesto nerviosos con mis opiniones sobre el Covid y el Covidismo. Aunque no han llegado a abrirme un expediente como la Universidad, sí me han comunicado que no publicarán mas artículos míos sobre cosas pandémicas. En fin, la censura va que cabalga orgullosa y controlando, como la Bestia Trionfante.

Muy bien Vox contra el pasaporte Covid, contra los abusos del despotismo sanitario y contra la vacunación obligatoria.

AHORA BIEN, en Vox no se han opuesto a la OBLIGATORIEDAD de la mascarilla, medida abusiva, inútil, ridícula, indigna y HUMILLANTE. Ahí no emplean su criterio ni su defensa de las libertades y de la cultura y tradición española, NO AFGANA.

Tampoco han manifestado ningún interés por los efectos negativos de las vacunas—como si fuese un problema del cual se puede uno desentender así sin más. Vermos si esto va a más, como es muy de temer, y si se hace insostenible seguir ignorándolo.

¡¡PÓNGANSE LAS PILAS SEÑORES, QUE PARA ESTAR DE PERFIL YA TENEMOS A MUCHOS OTROS!!

—oOo—

En bucle pic.twitter.com/GUyxr93LWP

— Noelia de Trastámara (@N_Trastamara) November 20, 2021

Davis, Ian. "Covid-19 Evidence of Global Fraud." Off-Guardian 17 Nov. 2021.*https://t.co/QnmSCP76Tv

— JoséAngelGarcíaLanda (@JoseAngelGLanda) November 22, 2021

2021

______. "Evidencia de fraude global Covid-19." Biblioteca Pléyades https://t.co/NRTdOF5h0d

2021

OJO A INGLATERRA: Los vacunados Covid menores de 60 tienen mortalidad DOBLE a los no vacunados. NO SE VACUNEN. https://t.co/ufLeNY37IK

— JoséAngelGarcíaLanda (@JoseAngelGLanda) November 22, 2021

PS: Médicos por la verdad americanos han logrado la

publicación de los informes internos que Pfizer quería esconder durante

55 años. Éste es el primero, con decenas de miles de víctimas, más de

1200 mortales.

Pfizer. (With Worldwide Safety). "5.3.6 CUMULATIVE ANALYSIS OF POST-AUTHORIZATION ADVERSE EVENT REPORTS OF PF-07302048 (BNT162B2) RECEIVED THROUGH 28-FEB-2021." Online at Public Health and Medical Officials for Transparency. (Nov. 2021).*

https://phmpt.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/5.3.6-postmarketing-experience.pdf

2021

—oOo—

Este artículo lo ha censurado SSRN al poco de colgarlo. No me lo deja colgar ni en la sección de artículos personales. Me comunica educadamente un tal Travis W., esbirro de la voz de su amo:

Thank you for your interest in submitting your paper to SSRN. Given the need to be cautious about posting medical content, SSRN is selective on the papers we post. Your paper has not been accepted for posting on SSRN.

Y le contesto:

I see the long tentacles of globalist interests reach out into SSRN, and you keep on censoring academic freedom of thought. Shame on you. I suppose it is only to be expected when one sees on your cover "race" as a promoted item with a fist. NAUSEATING, that's the state American freedoms are in.

Encima el sistema tiene la cara dura de decirme que lo he eliminado yo, "Removed by Author" (Eso es que la censura ni entraba inicialmente en sus planteamientos, pero todo va cambiando). Aquí se ve la lista de las cosas que les alarman y que tienen que censurar para protegernos de ideas peligrosas y de contagios del pensamiento independiente:

El artículo puede leerse en Academia, que de momento no censura estas cosas—aquí:

El alarmismo pandémico de la Covid-19: Una bibliografía

—oOo—

Ver aquí: https://youtu.be/3123lHT_dfc

Quién nos hubiera dicho que esta moza acabaría transformada en semejante perniciosa covidiana. Ahora nos quiere imponer el pasaporte de vacunación, y si le dejan, la inyección obligatoria en modo Menguele. Todo por nuestro bien, claro, todo para el pueblo, pero sin el pueblo.

______

Un análisis penetrante y aguzado de la situación nos propone el conde de Rochester:

García Landa, José Angel. "Experimental Darts (The Famous Pathologist)." In García Landa, Vanity Fea March 2022.*

https://vanityfea.blogspot.com/2022/03/experimental-darts-famous-pathologist.html

2022

—oOo—