martes, 28 de febrero de 2017

Starmania en retroprospección

La era Trump vista desde los años 70. Starmania es una memorable comedia musical de los años 70, aquí en la versión de 1989. Muestra entre otras cosas un mundo globalizado y despersonalizado por las franquicias, con la opinión pública manipulada por los medios, y con un gran constructor y financiero, Zéro Janvier, que desde la torre que lleva su propio nombre inicia una mediática carrera para volverse Presidente de Occidente—predicando que hay que cerrar las fronteras a la inmigración, y explotando el terror a los atentados terroristas de los Estrellas Negras. Estos son a la vez criminales, revolucionarios anarquistas, y rebeldes mimados disidentes del mismo sistema que los ha creado, del que son a la vez peleles, enemigos, parásitos, y víctimas.

Y en medio, entre una población de la decadente sociedad postindustrial, manipulada por los reality shows y la telebasura, vemos la soledad de los individuos, alienados, descontentos y frustrados por el teatro urbano en el que se ven atrapados—desde la camarera automática, pasando por la estrella pop alienada en su propia imagen multiplicada, hasta el mismo magnate mediático... que hubiera querido ser artista.

Y en medio, entre una población de la decadente sociedad postindustrial, manipulada por los reality shows y la telebasura, vemos la soledad de los individuos, alienados, descontentos y frustrados por el teatro urbano en el que se ven atrapados—desde la camarera automática, pasando por la estrella pop alienada en su propia imagen multiplicada, hasta el mismo magnate mediático... que hubiera querido ser artista.

—oOo—

Hitler y Bush: Dos pintores aficionados

Min. 25. Hitler, de pintor a montar guerras de agresión. Bush, más positivo: de montar guerras agresivas, a pintor. https://t.co/RIPSM7RDWE— JoseAngelGarcíaLanda (@JoseAngelGLanda) 28 de febrero de 2017

—oOo—

Planète, Chordified

No sé cómo van a parar a Chordify mis vídeos musicales, pero el caso es que de vez en cuando aparecen por allí. Aquí está una versión de Planète (canción que le pillé a un disco de Juliette Gréco de hace veinte años). Una cosa, para guitarristas aficionados: si los acordes no corresponden a lo que pone en la página, es, naturalmente, porque la toco con cejilla.

Otra más si no tienen bastante: Me & Bobby McGee, con sus acordes.

—oOo—

Una obscenidad pública

Jiménez Losantos, Federico. "Federico a las 6: El

colegueo de Soraya con los golpistas." Libertad

Digital 28 Feb. 2017.*

2018

—oOo—

Retropost #1479 (28 de febrero de 2007): Aspirando a cátedras

Aquí están los resultados de la última prueba de habilitación para cátedras de Filología Inglesa (primer ejercicio, en Granada).

Código de habilitación: 1/345/2005

RESULTADOS DE LA PRIMERA PRUEBA

Nombre y Número de votos

1. ACUÑA FARIÑA, JUAN CARLOS 7

2. AMORES CARREDANO, JOSÉ GABRIEL DE 2

3. BARBEITO VARELA, JOSÉ MANUEL 1

4. BRUTON, ANTHONY STEWART 1

5. CARRERA SUÁREZ, MARÍA ISABEL 4

6. COMESAÑA RINCÓN, JOAQUÍN 2

7. CONDE SILVESTRE, JUAN CAMILO 5

8. CORTÉS RODRÍGUEZ, FRANCISCO JOSÉ 4

9. CUDER DOMÍNGUEZ, MARÍA PILAR 1

10. DAVIS GARCÍA, ROCÍO MARÍA 6

11. DÍAZ FERNÁNDEZ, JOSÉ RAMÓN 1

12. DURÁN GIMÉNEZ-RICO, MARÍA ISABEL 2

13. FUERTES OLIVERA, PEDRO ANTONIO 2

14. GÓMEZ LARA, MANUEL JOSÉ 2

15. GURPEGUI PALACIOS, JOSÉ ANTONIO 5

16. HERNÁNDEZ CAMPOY, JUAN MANUEL 4

17. INCHAURRALDE BESGA, CARLOS 2

18. JIMÉNEZ HEFFERNAN, JULIÁN SEBASTIÁN 4

19. LLINAS I GRAU, MIREIA 3

20. LÓPEZ GARCÍA, DÁMASO 1

21. MARÍN ARRESE, JUANA ISABEL 5

22. MEDINA CASADO, CARMELO JOSÉ 1

23. MOTT, BRIAN LEONARD 2

24. NEFF VAN-AERTSELAER, JOANNE 4

25. POSTEGUILLO GÓMEZ, SANTIAGO 2

26. PRIETO PABLOS, JUAN ANTONIO GERMÁN 1

27. RABADÁN ÁLVAREZ, ROSA 5

28. ROMERO TRILLO, JESÚS 2

29. SÁNCHEZ-PARDO GONZÁLEZ, ESTHER 2

30. VARELA ZAPATA, JESÚS 1

Al parecer, hay treinta personas que aspiran a tener una cátedra de Filología Inglesa en España. Me refiero a que (de los muchos más que seguramente aspiran) son treinta los que de hecho se han presentado a la última habilitación. Como se ve por los resultados, son muchos los presentados y pocos los elegidos: los tribunales parecen tener morro fino y no creen que la mayoría de los colegas merezcan un pase; siete votos no merece más que uno, y eso que aún estamos en la primera prueba. No es por criticar ni a los más votados ni al tribunal (pues no sé qué sistema siguen de votación, y los resultados puede que sean inesperados para todos)… pero me parece que los resultados no son muy indicativos de la calidad relativa de los candidatos. Tampoco voy a dar ejemplos, y tampoco los conozco a todos, pero la impresión que me produce es que esto de las habilitaciones tiene mucho de lotería. Sobre si están las bolas trucadas, lo desconozco y no lo voy a decir por tanto: pero sería indicativo saber en qué universidades han salido las plazas que se van a ocupar, y si hay alguna relación entre esa ubicación y los resultados de la habilitación. Las malas lenguas (entre las que me incluyo) dicen que suele haberla; insisto en que no sé nada de esta convocatoria en particular. Si alguien sabe, pues que comente. Mi experiencia directa de los exámenes de cátedras (antes de que se introdujeran las habilitaciones) no puede ser más negativa.

Los resultados de las habilitaciones parecen ser más bien un cubrir un expediente: seguro que los candidatos propuestos tienen un excelente currículum, y salen habilitados, y quedan cubiertas las plazas, quod erat desiderandum para el Ministerio. Además, probablemente las acabarán ocupando en la mayoría de los casos los candidatos más apoyados. Y los demás, viento fresco, a la siguiente si no se han quemado aún. La de gente que pierde el tiempo con estas convocatorias… Yo me juré no perder en habilitaciones ni un minuto: están verdes, pero verdísimas. Sin apoyo en tu propia universidad, sin el elemento de suerte, y sin un currículum que tumbe de espaldas, no hay nada que hacer. Si hay telefonazos subterráneos que ayuden... pues aún mejor. El trabajo y la capacidad así a lo tonto no aseguran nada de nada. Pero mientras tanto está la profesión entretenida con esta zanahoria, y se ha echado el alto de hecho durante años, o para siempre, a la promoción de toda una generación especialmente numerosa y especialmente bien preparada en Filología Inglesa. Lo malo es que muchos puede que interpreten su único voto obtenido, o dos votos, como un resultado injusto para toda una carrera. Y bien puede que, en suma, todo este sistema sea más contraproducente que producente.

En fin, enhorabuena a los mejor situados… y a los demás, mejor los desanimo que los animo; animarles a volver a presentarse sería flaco favor, creo, en un sistema de promoción tan engañoso y malgastador de energías. Que esperen a las acreditaciones, a ver si pintan mejor, aunque lo dudo. Y sin embargo aquí como en todo se aplica una regla: el que la sigue la consigue. Ahora bien, para llegar a tener una cátedra, he observado, hay que seguir muchas normas y protocolos que no figuran en el libro, ni en el baremo oficial de los tribunales.

Gramática parda

—oOo—

lunes, 27 de febrero de 2017

Vuelve el 11-M

Jiménez

Losantos, Federico. "Federico a las 6: La vuelta del 11-M." EsRadio 27 Feb. 2017.*

2017

—oOo—

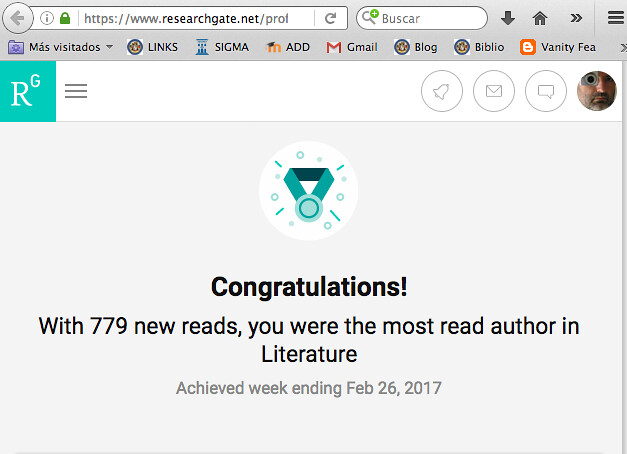

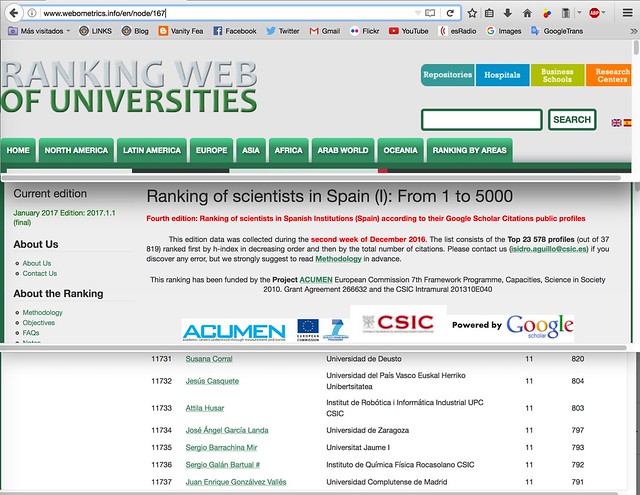

Destaco en Literatura, Lingüística y Estética

Rank 11734

Según la Ranking Web of Universities, en su sección "Ranking of Scientists in Spain", estoy en el puesto 11.734. No lo digo por destacado, que no lo es, claro...

... pero bueno, a ver si nos vamos moviendo para arriba o para abajo en otra edición. Este proyecto de ránking es español y se basa en el índice h de Google Scholar (que ahora mismo estoy en un 11 ahí, como se echa de ver).

Con otros criterios más halagüeños tengo posicionamientos mejores, y con otros criterios que me gustan menos, otros todavía peores, sin duda. Pero este ránking de Google lleva camino de oficializarse casi, por lo que veo.

—oOo—

Altísima traición desde la cumbre

¿Dónde eso? Busquen nada más en Google, o donde sea, "Juan Carlos I Marcha Verde" —y vean lo que ven.

España pactó en secreto con Marruecos la organización de la Marcha Verde y la entrega del Sáhara español—que entonces era, no lo olvidemos una provincia española, no una colonia.

Vivimos en un país tan envilecido que esto ni siquiera se ha comentado, a resultas de su reciente desclasificación en los papeles de la CIA. Es inútil plantearse qué haría un gobierno español digno de tal nombre en esta situación, y con esta información, porque no lo va a haber.

Pero entregar un tercio del territorio nacional, para inaugurar el reinado, es no sólo una inauguración que marca el tono de lo que va a seguir, sino un acto de altísima traición, exhibida con luces de neón ante un país embrutecido y aborregado. Que nunca va a pasar cuentas—distraído y convenientemente desactivado por sus demás problemas de secesión interna, cuidadosamente mimados y alimentados desde el gobierno central.

Qué vergüenza y qué infamia. Con antecedentes así, disimulados y sin desautorizar, vamos avisados: nadie está a salvo de que el gobierno arríe la bandera de cualquiera de sus provincias, y anule los DNIs de los españoles allí residentes. Con mucho pacto secreto previo, eso sí.

—oOo—

Retropost #1478 (27 de febrero de 2007): Johnson contra Milton: Machismo y censura

Mucho es, desde luego, llamar a Samuel Johnson "feminista". Y sin embargo, al comentar la obra de Milton, hace observaciones sobre el patriarcado militante de este autor que no son corrientes en un crítico de su época, anticipándose a cosas que diría la crítica feminista siglos después. Cierto es que a Johnson, defensor de la ley y el orden, y de la Iglesia establecida, le horrorizaba la política de Milton, y eso parece que le hacía más sensible a otros aspectos que veía criticables en su carácter e ideas:

Me

temo que el republicanismo de Milton estaba fundado sobre un odio

envidioso a la grandeza, y un hosco deseo de independencia; sobre una

petulancia impaciente con quienes le controlaban, y un orgullo desdeñoso

hacia sus superiores. Odiaba a los monarcas en el Estado, y a los

prelados en la Iglesia; pues odiaba a todos a quienes se veía obligado a

obedecer. Es de sospechar que su deseo predominante era destruir, más

bien que establecer, y que no sentía tanto amor por la libertad como

repugnancia hacia la autoridad.

Se ha observado que quienes con más ruido claman por la libertad, no la conceden de buena gana. Lo que sabemos del carácter de Milton en las relaciones domésticas es que era severo y arbitrario. Su familia estaba compuesta de mujeres; y aparece en sus libros una especie de desprecio turco hacia las hembras, como seres subordinados e inferiores. Para que sus propias hijas no se saliesen de las filas, permitió que se viesen deprimidas con una educación mezquina y tacaña. Pensaba que la mujer estaba hecha únicamente para la obediencia, y el hombre únicamente para la rebelión.

Se ha observado que quienes con más ruido claman por la libertad, no la conceden de buena gana. Lo que sabemos del carácter de Milton en las relaciones domésticas es que era severo y arbitrario. Su familia estaba compuesta de mujeres; y aparece en sus libros una especie de desprecio turco hacia las hembras, como seres subordinados e inferiores. Para que sus propias hijas no se saliesen de las filas, permitió que se viesen deprimidas con una educación mezquina y tacaña. Pensaba que la mujer estaba hecha únicamente para la obediencia, y el hombre únicamente para la rebelión.

Cuando habla del machismo de las obras de Milton piensa sin duda Johnson ante todo en la subordinación de Eva a Adán que tanto se enfatiza en Paradise Lost. El retrato de Adán tiene allí mucho de autobiográfico... sólo que Milton se consideraba, sin duda, un Adán perfeccionado, que ataba más corto a su mujer.

También disiente Johnson de Milton en cuanto a la libertad de prensa que defendía éste. Una libertad de prensa que en lo legal llegó a Inglaterra en cierta medida a finales del siglo XVII (antes la hubiese querido Milton, que publicó su Areopagitica sin licencia previa). Y en la práctica efectiva, quizá sólo haya llegado la libertad de prensa con los blogs, si eso es prensa.... o quizás siempre esté por llegar. En cualquier caso, Milton se oponía a la censura (con importantes excepciones, sin embargo) y Johnson defiende la necesidad política de la censura y no admite la libertad de prensa:

Por entonces publicó su Areopagitica: Discurso del Sr. John Milton en favor de la Libertad de Prensa sin Licencia. El peligro de semejante libertad sin límites, y el peligro de limitarla, han producido un problema en la ciencia del gobierno que el entendimiento humano parece hasta hoy incapaz de resolver. Si no se puede publicar sino lo que la autoridad política haya aprobado antes, el poder habrá de ser la medida de la verdad; si cada soñador de innovaciones puede propagar sus projectos, no puede haber orden seguro; si cada murmurador contra el gobierno puede difundir el descontento, no puede haber paz; y si cada escéptico en cuestiones de teología puede enseñar sus necedades, no puede haber religión. El remedio contra estos males es castigar a los autores; pues todavía se admite que la sociedad puede castigar, aunque no impedir, la publicación de opiniones que esa sociedad considere perniciosas. Pero este castigo, aunque aplaste al autor, promociona el libro; y no parece más razonable dejar el derecho de publicación sin restricciones por el hecho de que se pueda después reprender a los autores, de lo que parecería el dormir con las puertas sin cerrojo, por el hecho de que después se pueda ahorcar a los ladrones.

—oOo—

domingo, 26 de febrero de 2017

Bob Dylan - Abandoned Desire (Desire Sessions)

From Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands:

New video again, this time with the Desire Sessions. Although it is not as revered as Blood On The Tracks, Desire is still one of Dylan's strongest albums with incredible songs like the protest song Hurricane about Rubin Hurricane Carter, a black boxer wrongfully accused of murder. The song launched the Rolling Thunder Revue across New England to plead for his release from prison, culminating with a concert at Madison Square Garden and another inside Hurricane's jail. You also have songs like Isis, Romance in Durango, Oh, Sister, and finally Sara. The last song is obviously dedicated to his then wife Sara, when the couple was in a midst of breaking up (which will happen two years later).

Not many outtakes are circulating from that album however, albeit from an alternate version of Hurricane, and alternate takes of Joey and the single Rita May. Other outtakes exist but were released on Bootleg Series Vol. 1-3 (Catfish, Golden Loom) and the magnificent Abandoned Love on Biograph.

On this bootleg, you will find the quadrophonic version of the album (the original intended mix but since the technology didn't allow a large release, the album was consequently available only on stereo with another mix). You will also have some live recordings of the album through the years, and of course most of the outtakes of Desire.

Another surprise is the session Bob had with Bette Midler for her album Songs From The New Depression with Nuggets of Rain (a spoof of Buckets of Rain from Blood On The Tracks) and the complete rehearsal of that song (with Bob talking, working, and sometimes flirting with Bette Midler).

Here is the tracklist:

Quadraphonic Desire

1. Hurricane

2. Isis

3. Mozambique

4. One More Cup Of Coffee (Valley Bellow)

5. Oh, Sister

6. Joey

7. Romance In Durango

8. Black Diamond Bay

9. Sara

10. Hurricane (Live - Clinton Correctional Institute, Dec 7, 1975)

11. Romance In Durango (Live - Hammersmith Apollo, Nov 24, 2003)

12. Abandoned Love (Live - The Other End, July 3, 1975)

Abandoned Desire

1. Joey (Alternate Take)

2. Rita May (Single Version)

3. Catfish

4. Golden Loom

5. Hurricane ("Libel" Version)

6. Rita May (Alternate Take)

7. Abandoned Love

8. People Get Ready

9. Nuggets Of Rain

10. Rehearsal Dialogue

11. Buckets Of Rain

12. Joey (Alternate Take) [Corrected]

Credits to Dylanstubs.com for the pictures and bjorner.com for the information.

—oOo—

Retropost #1477 Implied author(s) in film and literature

Lunes 26 de febrero de 2007

Implied author(s) in film and literature

My reply to a question in the Narrative-List (from Ellen Peel, San Francisco State University) concerning the possibility of multiple implied authors in film and fiction:

On the issue of implied authors in film / novel:

Perhaps two separate issues need clarification.

1) If the implied author is taken to be an interpretive construct, and is as such dependent on a reader's construction of the text, it is of course to be expected that different readers may construct different implied authors (or different implied authorial values, attitudes, etc.). That would seem to apply to both written fiction and film.

2) Perhaps the term is not ideal for use in film studies, given that it is an import from literature, and is as such tailor-made for the standard literary situation in fiction, that is: a text as the product of an individual author. That said, there may be much more common ground than this would lead us to assume, in particular in marginal or non-standard cases: auteur film, pseudonymous multi-authored novels, etc.

As to myself, I think that "showing" (a story, values, etc.) the way a film does may be more conducive to multiple constructions of intent, value, etc.; and that would seem to provide a rationale for "multiple implied authors" as in (1) above. But a given interpretation of an individual case need not assume multiple implied authorship in the sense of a multiplicity or indeterminacy of authorial stance, implied values, political outlook, etc . "Collaborative authorship" is quite a different problem—though not without interesting connections with this issue, I should say.

Among the replies, Marie-Laure Ryan wrote:

> The posts on the implied author in film seem to take it for granted that the notion of implied author is essential to the understanding of verbal narrative; but in fact its theoretical necessity is far from established. See the entry "implied author" in the Routledge Encylopedia of Narrative, as well as the recent book by Tom Kindt and hans Harald Mueller, The Implied Author: Concept and Controversy," Berlin: Walter De Gruyter 2006.

My reply to the list (Feb. 27):

There is much debate on the implied author, to be sure. The argument that we need to get rid of "anthropomorphic" concepts in textual analysis has alwas struck me as a surprising one, though, given that only anthropomorphic creatures communicate through texts.

As to the Routledge Encyclopedia article on the matter, it concludes that it is a problematic concept which continues to generate controversial debate, which is probably true. On the way, though, the article seems to take for granted a definition of the implied author as "a 'voiceless' and depersonified phenomenon . . . which is neither speaker, voice, subject, nor participant in the narrative communicative situation" —which does not seem to have much to do with Booth's original notion. The implied author should be understood as a communicative textual voice: the one responsible for the text as a whole, as an intentional communicative (and rhetorical, and artistic) construct. The implied author is far from silent: s/he speaks using the protocols and conventions of literary and narrative communication—and this does not seem to be part of the assumptions of many of the critics of the concept. No wonder such a concept (of their own making, I should say) will appear to be controversial or problematic!

On the other hand, film, while being a narrative phenomenon, cannot be reduced to a linguistic communicative situation. And that may account for some of the problems which crop up when the concept of the implied author is applied to film. There is much common ground, but also some significant differences.

The conversation goes on... Marie-Laure RYAN writes:

> When I was young and gullible and soaked up the theory of the day uncritically, I did not dare use the a-word “author” in my papers for fear of being laughed at as hopelessly naive: haven’t Barthes and Foucault convincingly demonstrated that the author is dead? Isn’t intention a fallacy and shouldn’t the text be a self-enclosed system of meaning? Whenever I had to mention the author, I prefixed the a-word with “implied” and that was much more respectable. Yet, I don’t see why I cannot attribute intents/beliefs/values to the author(s) rather than to a mysterious “implied” double of the author. Sure, the author as I imagine him/her is my own construction, but do I imagine a human being who writes a text, or do I imagine an abstract theoretical entity whose sole reason to exist is to prevent the real author from expressing opinions? Is it illicit to ask questions about what the author might have meant when reading a text? And is it illicit to use one’s knowledge about biographical authors and what one knows of their other works when interpreting a text? When I say that in the late works of Camus there is a mystical trend that is not present in the earlier works, am I speaking of an “implied” or am I attributing a change in world-view to Camus himself? And finally, about the anthropomorphic question: if I attribute belief, intents, values, etc. to an author, whether implied or real, then of course this will be an anthropomorphic construct. Pure theoretical constructs do not have a mental life.

>

> As for language-dependency: I think that narration is a verbal act, so I would get rid of the concept of narrator in any mimetic form of narrative (drama, film, compute games) and retain it for the diegetic forms. It is perhaps unfortunate that our field of narratology developed as the study of literary narrative and is burdened with terms that presuppose language. In fact, even ordinary language does: one speaks of storytelling. So it seems natural to ask: who tells? But what would narratology be like if instead of story-telling one spoke of story-showing, which is much more appropriate for film and drama?

> If there are narrators in fim, besides the source of voiced-over narration, are there narrators in drama, and who are they?

Answer:

Dear Marie-Laure: more views on the implied author...

- Yes, one may attribute values, a world-view, etc., to the author; only, insofar as you are doing that on the basis of a given work, you are attributing them to the implied author of a work. In many contexts there is no practical sense in differentiating the two, but sometimes you do need the implied author: if a socialist writer is forced to write conservative pamphlets, say, for his job, then you need to differentiate the ideology of the writer of those pamphlets (an implied author, possibly a pseudonymous or anonymous writer or a ghost-author) from the person who holds other beliefs in other contexts and perhaps in other works.

- And, as to narration: VERBAL narration is a verbal act, but narration in images, in choreographed action-verbal or otherwise-as in drama, is not a verbal act, it is a compositional act. If the net result is a narrative, though (in the extended sense of "a sequential representation of a sequence of actions, etc.") it makes some sense to speak of the act of composition as a narrative act, even though the term "narration" does create some confusion. Anyway, there is lot of verbal storytelling in drama and in film, but what makes these genres central to narratology is not that verbal storytelling they include: it is, rather, the fact that dramatic and cinematic composition is a narrative act (though not a verbal act).

PS: In early March, the debate goes on. In a message I've lost, M.-L. Ryan notes that narratologists do not usually include in their toolkit both the author and the implied author, and that in any case they do not use the implied author in order to explain such cases as unreliable narration, etc. In her example, although Booth would interpret the implied author of A Modest Proposal to be an ironist rather than an advocate of cannibalism, this is not the use which is made of the concept nowadays: narratologists would assume the implied author is in favour of eating babies... My answer:

Dear Marie-Laure:

- It is perhaps the case that some (or many) narratologists do not use the concept of implied author to analyze such cases as unreliable narrators, ghost writing, etc. Well, I don't think such analyses can go very far, for they would lack an essential concept. Which is in any case no more than a tool, to be used in practical analysis of a given text as flexibly as necessary. But sometimes you just need a monkey wrench, or whatever: in literature, you need implied authors all the time. Which shouldn't lead us to forget real authors: if narratologists (not me!) do that all the time, bad for them. Such narratological analyses will be restricted to a predefined set of laboratory phenomena, and will not deal with the actual dynamics of communication.

As to the Swift example: that would be, for Booth, the standard case in which we need to use the concept of an implied author. Of course someone may interpret that the implied author is advocating cannibalism... but that would be a misreading of the text, one which of course Swift invites in order to let his audience classify themselves between those who know how to read and those who don't... but I shouldn't expect narratologists to fall in the second group!

Dear Jose,

Back from a short trip, this explains why I haven't posted on the list. A few thoughts on the implied author: if the implied author of "A Modest Proposal" is NOT the one who advocates Cannibalism, as I thing Booth would say, what are we going to call the one who advocates cannibalism? For surely they should be differentiated. But if we do differentiate them, we add one more entity to that already cumbersome model of author-implied author-??-narrator.

My stance of this is as follows: ALL utterances--whether literary or not, fictional or not--have an implied speaker and a real speaker. The implied speaker is the one who fulfills the felicity conditions of the speech act taken literally. It is the speaker in Swift who advocates cannibalism. This implied speaker never lies, never uses irony or sarcasm. Then there is the real speaker, constructed by the hearer on the basis of the content of the utterance, the context, what he knows about the personality of the speaker and his intent in producing the speech act. Of course this speaker is inferred--we cannot read minds--but this speaker is assumed to be a real person. Sometimes the implied speaker and the real speaker differ, sometimes they do not. They differ not only in the case of irony and lie, but also in the case of incompatence: "I know what you mean, even though it's not what you said."

In literature--fiction, to be more precise--we add a narrator. The narrator tells the story as true, while the author does not. That's why we need the concept of narrator even in 3rd person. But why do we need to add the concept of an implied author who is neither the narrator not the real author? Is the implied author specific to literature? To fiction? Do we need him in a biography of Napoleon?

I said above we need an implied speaker in ordinary language to distinguish lie from sincere language and irony from literal language. It would seem then that we need him in fiction too, since such ways of speaking do occur in novels. But it seems to me that there is no need to add an implied author: irony and lies and unreliability can be attributed to the narrator. But narrator's irony can be transferred to author when narrator is not an individuated human being. So my model of what the reader needs to imagine goes like this:

1 Author(what author means)--2 Narrator (what narrator means)--3 Implied narrator (what narrator says literally), with 1 and 2 collapsing in non-fiction, and 2 and 3 collapsing in straighforward expression.

The concept of imnplied author would only be useful if it were potentially distinct from real author AND the reader would be able to judge the difference, but since advocates of the implied author forbid attributing any belief and intent to the real author, the notion becomes totally non-operational.

I guess my main gripe about much of what is done in narratology is that it is trying to complicate rather than simplify things and does not adhere to the principle of Ockham's razor. The implied author, to me, is a hedge that critics use to avoid committig themselves to saying anything about the authoir. And yet, critical literature is full of "Austen tells us that", "Sartre teaches us that," etc. Is there something to be gained by outlawing these expressions?

The whole discussion of the number of implied authors in film takes the theory to its absurd limits! Will we some day have multiple unreliable implied authors in painting?

Cheers

Marie-Laure

Dear Marie-Laure,

I hope you've had a nice trip. And thanks for answering in such detail to my ruminations: if you don't mind an additional spell of intellectual ping-pong, I'll answer back between the lines:

> Dear Jose,

> Back from a short trip, this explains why I haven't posted on the list. A few thoughts on the implied author: if the implied author of "A Modest Proposal" is NOT the one who advocates Cannibalism, as I thing Booth would say, what are we going to call the one who advocates cannibalism? For surely they should be differentiated. But if we do differentiate them, we add one more entity to that already cumbersome model of author-implied author-??-narrator.

Well, as I take it, we would call the one who advocates cannibalism "the narrator" or perhaps "the speaker" since this is not a narrative proper. And the one who doesn't, the implied author. Whom we know as Swift, or rather, Swift-in-his-text. Should Swift have advocated cannibalism in his final madness, that would be a matter relevant to the biographical author, not to the implied author of this text. Anyway, we are constructing, perhaps, a simplified model of Swift's irony here, for the sake of the argument, because the actual Modest Proposal, or Gulliver, or any other text by Swift, exhibit ambiguities and imperceptible transitions between voices which would need to be analysed in greater detail.

> My stance of this is as follows: ALL utterances--whether literary or not, fictional or not--have an implied speaker and a real speaker. The implied speaker is the one who fulfills the felicity conditions of the speech act taken literally. It is the speaker in Swift who advocates cannibalism. This implied speaker never lies, never uses irony or sarcasm. Then there is the real speaker, constructed by the hearer on the basis of the content of the utterance, the context, what he knows about the personality of the speaker and his intent in producing the speech act. Of course this speaker is inferred--we cannot read minds--but this speaker is assumed to be a real person. Sometimes the implied speaker and the real speaker differ, sometimes they do not. They differ not only in the case of irony and lie, but also in the case of incompatence: "I know what you mean, even though it's not what you said."

I agree, of course, though there are some terminological problems. In your account here, the "implied speaker" of an ironic utterance is not using irony (Swift's cannibal), while the "real speaker" of an ironic utterance is the ironist (Swift). The problem is that (as you stated before concerning the differences with Booth's usage) your "implied" refers to the level would call the (unreliable) narrator, and your "real" refers to Booth's implied plus real author. This is understandable, because any speaker/writer is "implied" in his text: the cannibal in his cannibalistic text, and the ironist in his ironic text, when read as irony.

> In literature--fiction, to be more precise--we add a narrator. The narrator tells the story as true, while the author does not. That's why we need the concept of narrator even in 3rd person. But why do we need to add the concept of an implied author who is neither the narrator not the real author? Is the implied author specific to literature? To fiction? Do we need him in a biography of Napoleon?

Not specific to literature; this is a matter of general communication, especially writing. In a biography of Napoleon? Well... perhaps. It depends on what you are trying to do. If you are comparing the author-in-the-text (implied author) to another expression or text of the same author, you might need to distinguish the author you construct on the basis of this text from the one you construct on the basis of his journalistic articles, etc.

> I said above we need an implied speaker in ordinary language to distinguish lie from sincere language and irony from literal language. It would seem then that we need him in fiction too, since such ways of speaking do occur in novels. But it seems to me that there is no need to add an implied author: irony and lies and unreliability can be attributed to the narrator.

OK, fictional narrators can do anything authors can do (since fictional narrative may be motivated as fictional authorship). But in order to interpret unreliability, you need to contrast the unreliable narrator (e.g. Jason in The Sound and the Fury) with someone who holds a reliable moral (intellectual, etc.) position: and that is the author. The author-in-the-text, as you construct his position, that is, the implied author. ("Faulkner", for Booth). If you're a good reader, you don't read Jason's text as being endorsed by the author, you read an implied evaluation between the lines. And insofar as that is a textual, implied, constructed position, we're speaking of an implied author, irrespective of our knowledge of other Faulkner texts or anything about Faulkner as a person ("the real author") apart from this novel.

> But narrator's irony can be transferred to author when narrator is not an individuated human being. So my model of what the reader needs to imagine goes like this:

> 1 Author(what author means)--2 Narrator (what narrator means)--3 Implied narrator (what narrator says literally), with 1 and 2 collapsing in non-fiction, and 2 and 3 collapsing in straighforward expression.

> The concept of imnplied author would only be useful if it were potentially distinct from real author AND the reader would be able to judge the difference, but since advocates of the implied author forbid attributing any belief and intent to the real author, the notion becomes totally non-operational.

But it is potentially distinct from the implied author, there are many possible examples in which it is not only operational, but necessary. Unwanted juvenilia. Recantations. Conversions. Etc.—to take just one possible line of difference. I don't know about "advocates of the implied author", but Booth, in Critical Understanding, often contrasts the implied author in a given work and the author in other works or communicative interactions. And me too!

> I guess my main gripe about much of what is done in narratology is that it is trying to complicate rather than simplify things and does not adhere to the principle of Ockham's razor.

But sometimes we need to multiply the entities in order to deal with a complex case, because in verbal art, art consists in a multiplication of such levels of utterance. So, I'm all for simplification, but where it is advisable, or possible, one should not simplify one's toolkit so that an essential tool is missing. BTW, I read the other day an interesting paper (almost a hundred years old) on Ockham's razor: I'm enclosing it in case you feel curious about it.

> The implied author, to me, is a hedge that critics use to avoid committig themselves to saying anything about the authoir. And yet, critical literature is full of "Austen tells us that", "Sartre teaches us that," etc. Is there something to be gained by outlawing these expressions?

I'm not at all for outlawing. Rather, we need to speak of the author as a figure in the text, the "implied author" and as someone who has designed (not always in a fully conscious or controlled way) the appearance and features of such a figure, and that would be "the author". The one who is bored to death with writing potboilers is also the author, not the implied author!

> The whole discussion of the number of implied authors in film takes the theory to its absurd limits! Will we some day have multiple unreliable implied authors in painting?

Hahah! well you never know! That's beyond myself for the moment, though. As to film, yesterday I read at the end of the credits in a theater, "Columbia Pictures is the Author of this film"... so yet one more candidate, and an authoritative one! Cheers! JOSE ANGEL

Anyway, we both stood our ground in the end.

Thus far narrativeness or narrativity... Now for literariness. Fatemeh Nemati writes:

> Dear members of Narrative group

> Narratives told everyday everywhere by everyone are much similar to literaray narratives. It seems that they follow the same principle of representing the world. What makes the difference between a literary and a non-literary narrative if they are alike in every aspects of representing experiences of the real world? What happens to a narrative when it is branded as literary in contrast to non-literary? Do they differ in the meaning they convey or the way they convey it? Is it fictionality that promotes a narrative to the status of being literary rather than non-literary? Is it a magical transformation? How do you recognize that this narrative is literary rather than non-literary? are there yardsticks to measure it or are we again to depend on our intuition? What is the elixir that causes a narrative to transcend beyond the mundane reality, to enter the world of literature? I'm so perplexed that i feel i will die in the maze if nobody comes to my help. Kind regards

> Nemati

Dear Nemati:

I agree there is much common ground, certainly, between everyday conversational storytelling and literary narratives. In the last analysis, literary narrative derives from such oral stories. So there is in fact a continuum between literary and non-literary narratives. And what makes a story more or less literary (I would like to emphasize the "more or less", because it is not a matter of either/or, but a question of degree, context, etc.), what makes a story more or less literary is in part the use it is put to, and in part whether it shares a number of characteristics, none of which is in itself determinant. For instance, you mention fictionality, and well, yes, there is much common ground between literature and fiction, and a fictional conversational story would rate in principle as more "literary" than an instrumental one (conveying practical information, for instance). There are many other such parameters: whether a story has a status as a cultural icon or reference point (e.g. classical historical works, which nevertheless are supposed to be "factual"). Whether we are focusing on the story for the sake of narrative pleasure, and not for practical information. Whether the story uses language in a distinct, creative, rhetorically effective way. Whether it is tellable, repeatable... Whether it is written using literary conventions, and published as "literature". Etc. As I say, I see this as a number of criss-crossing parameters, none of which determines whether a story is to count as literary. The context of use is all-important. And the story's story: some stories are born literary, some become literary, and some have literariness thrown upon them!

Robert Scholes wrote:

The literary vs. non-literary distinction has nothing to do with fictional vs. real. It has to do with highbrow narrative vs. low-brow narrative, the stuff in "little" magazines vs. the stuff in "pulps," for example.

The distinction was used to distinguished "quality" fiction from cheap, popular stuff. Personally, I rejected that distinction long ago.

Bob Scholes

...and I reply:

There are many different notions as to what literature is, and many different contexts in which literature is distinguished from non-literature, so there is no way a clear-cut definition of literature can possibly be provided, from a "bird's eye view" of cultural phenomena. That doesn't mean that in a given context, or for one given person, the line between literature and non-literature may be quite sharply drawn; my point is that this would be just one context, or one notion, among many. That's why we need a fuzzy definition of literature according to a number of criss-crossing and grading scales.

Nonetheless, some notions are more widely shared than others, and some are more influential than others. For instance, more people would agree that "the book which inspired the film" is literature (good or bad, etc.), while "the film based on the book" is not literature (but film). And more people (more influential contexts, etc.) would agree that a highbrow, culturally valued text is literature, while a joke I happen to invent and tell my friends is not literature. Which is not to say that a given theorist may refuse to make that difference, in a given context. Or, again, many people will find it strange that Winston Churchill should be given the Nobel Prize for literature (quite apart from the quality of his style), while not many people will find it strange that Faulkner should be given the Nobel Prize for literature (whether they like his fiction or not), because "creative fictional writing" tends to be associated with literature in the minds of many people, while "history" tends to be put on another shelf by many people, libraries, bookstores, etc. I think it is useful to keep in mind which are the usual senses given to words, and uses given to books, whatever our theoretical preferences may be. Our theoretical proposals will have to intervene and make sense in (or try to change) that "real" cultural world, after all...

The list goes on...

Implied author(s) in film and literature

My reply to a question in the Narrative-List (from Ellen Peel, San Francisco State University) concerning the possibility of multiple implied authors in film and fiction:

On the issue of implied authors in film / novel:

Perhaps two separate issues need clarification.

1) If the implied author is taken to be an interpretive construct, and is as such dependent on a reader's construction of the text, it is of course to be expected that different readers may construct different implied authors (or different implied authorial values, attitudes, etc.). That would seem to apply to both written fiction and film.

2) Perhaps the term is not ideal for use in film studies, given that it is an import from literature, and is as such tailor-made for the standard literary situation in fiction, that is: a text as the product of an individual author. That said, there may be much more common ground than this would lead us to assume, in particular in marginal or non-standard cases: auteur film, pseudonymous multi-authored novels, etc.

As to myself, I think that "showing" (a story, values, etc.) the way a film does may be more conducive to multiple constructions of intent, value, etc.; and that would seem to provide a rationale for "multiple implied authors" as in (1) above. But a given interpretation of an individual case need not assume multiple implied authorship in the sense of a multiplicity or indeterminacy of authorial stance, implied values, political outlook, etc . "Collaborative authorship" is quite a different problem—though not without interesting connections with this issue, I should say.

Among the replies, Marie-Laure Ryan wrote:

> The posts on the implied author in film seem to take it for granted that the notion of implied author is essential to the understanding of verbal narrative; but in fact its theoretical necessity is far from established. See the entry "implied author" in the Routledge Encylopedia of Narrative, as well as the recent book by Tom Kindt and hans Harald Mueller, The Implied Author: Concept and Controversy," Berlin: Walter De Gruyter 2006.

My reply to the list (Feb. 27):

There is much debate on the implied author, to be sure. The argument that we need to get rid of "anthropomorphic" concepts in textual analysis has alwas struck me as a surprising one, though, given that only anthropomorphic creatures communicate through texts.

As to the Routledge Encyclopedia article on the matter, it concludes that it is a problematic concept which continues to generate controversial debate, which is probably true. On the way, though, the article seems to take for granted a definition of the implied author as "a 'voiceless' and depersonified phenomenon . . . which is neither speaker, voice, subject, nor participant in the narrative communicative situation" —which does not seem to have much to do with Booth's original notion. The implied author should be understood as a communicative textual voice: the one responsible for the text as a whole, as an intentional communicative (and rhetorical, and artistic) construct. The implied author is far from silent: s/he speaks using the protocols and conventions of literary and narrative communication—and this does not seem to be part of the assumptions of many of the critics of the concept. No wonder such a concept (of their own making, I should say) will appear to be controversial or problematic!

On the other hand, film, while being a narrative phenomenon, cannot be reduced to a linguistic communicative situation. And that may account for some of the problems which crop up when the concept of the implied author is applied to film. There is much common ground, but also some significant differences.

The conversation goes on... Marie-Laure RYAN writes:

> When I was young and gullible and soaked up the theory of the day uncritically, I did not dare use the a-word “author” in my papers for fear of being laughed at as hopelessly naive: haven’t Barthes and Foucault convincingly demonstrated that the author is dead? Isn’t intention a fallacy and shouldn’t the text be a self-enclosed system of meaning? Whenever I had to mention the author, I prefixed the a-word with “implied” and that was much more respectable. Yet, I don’t see why I cannot attribute intents/beliefs/values to the author(s) rather than to a mysterious “implied” double of the author. Sure, the author as I imagine him/her is my own construction, but do I imagine a human being who writes a text, or do I imagine an abstract theoretical entity whose sole reason to exist is to prevent the real author from expressing opinions? Is it illicit to ask questions about what the author might have meant when reading a text? And is it illicit to use one’s knowledge about biographical authors and what one knows of their other works when interpreting a text? When I say that in the late works of Camus there is a mystical trend that is not present in the earlier works, am I speaking of an “implied” or am I attributing a change in world-view to Camus himself? And finally, about the anthropomorphic question: if I attribute belief, intents, values, etc. to an author, whether implied or real, then of course this will be an anthropomorphic construct. Pure theoretical constructs do not have a mental life.

>

> As for language-dependency: I think that narration is a verbal act, so I would get rid of the concept of narrator in any mimetic form of narrative (drama, film, compute games) and retain it for the diegetic forms. It is perhaps unfortunate that our field of narratology developed as the study of literary narrative and is burdened with terms that presuppose language. In fact, even ordinary language does: one speaks of storytelling. So it seems natural to ask: who tells? But what would narratology be like if instead of story-telling one spoke of story-showing, which is much more appropriate for film and drama?

> If there are narrators in fim, besides the source of voiced-over narration, are there narrators in drama, and who are they?

Answer:

Dear Marie-Laure: more views on the implied author...

- Yes, one may attribute values, a world-view, etc., to the author; only, insofar as you are doing that on the basis of a given work, you are attributing them to the implied author of a work. In many contexts there is no practical sense in differentiating the two, but sometimes you do need the implied author: if a socialist writer is forced to write conservative pamphlets, say, for his job, then you need to differentiate the ideology of the writer of those pamphlets (an implied author, possibly a pseudonymous or anonymous writer or a ghost-author) from the person who holds other beliefs in other contexts and perhaps in other works.

- And, as to narration: VERBAL narration is a verbal act, but narration in images, in choreographed action-verbal or otherwise-as in drama, is not a verbal act, it is a compositional act. If the net result is a narrative, though (in the extended sense of "a sequential representation of a sequence of actions, etc.") it makes some sense to speak of the act of composition as a narrative act, even though the term "narration" does create some confusion. Anyway, there is lot of verbal storytelling in drama and in film, but what makes these genres central to narratology is not that verbal storytelling they include: it is, rather, the fact that dramatic and cinematic composition is a narrative act (though not a verbal act).

PS: In early March, the debate goes on. In a message I've lost, M.-L. Ryan notes that narratologists do not usually include in their toolkit both the author and the implied author, and that in any case they do not use the implied author in order to explain such cases as unreliable narration, etc. In her example, although Booth would interpret the implied author of A Modest Proposal to be an ironist rather than an advocate of cannibalism, this is not the use which is made of the concept nowadays: narratologists would assume the implied author is in favour of eating babies... My answer:

Dear Marie-Laure:

- It is perhaps the case that some (or many) narratologists do not use the concept of implied author to analyze such cases as unreliable narrators, ghost writing, etc. Well, I don't think such analyses can go very far, for they would lack an essential concept. Which is in any case no more than a tool, to be used in practical analysis of a given text as flexibly as necessary. But sometimes you just need a monkey wrench, or whatever: in literature, you need implied authors all the time. Which shouldn't lead us to forget real authors: if narratologists (not me!) do that all the time, bad for them. Such narratological analyses will be restricted to a predefined set of laboratory phenomena, and will not deal with the actual dynamics of communication.

As to the Swift example: that would be, for Booth, the standard case in which we need to use the concept of an implied author. Of course someone may interpret that the implied author is advocating cannibalism... but that would be a misreading of the text, one which of course Swift invites in order to let his audience classify themselves between those who know how to read and those who don't... but I shouldn't expect narratologists to fall in the second group!

Dear Jose,

Back from a short trip, this explains why I haven't posted on the list. A few thoughts on the implied author: if the implied author of "A Modest Proposal" is NOT the one who advocates Cannibalism, as I thing Booth would say, what are we going to call the one who advocates cannibalism? For surely they should be differentiated. But if we do differentiate them, we add one more entity to that already cumbersome model of author-implied author-??-narrator.

My stance of this is as follows: ALL utterances--whether literary or not, fictional or not--have an implied speaker and a real speaker. The implied speaker is the one who fulfills the felicity conditions of the speech act taken literally. It is the speaker in Swift who advocates cannibalism. This implied speaker never lies, never uses irony or sarcasm. Then there is the real speaker, constructed by the hearer on the basis of the content of the utterance, the context, what he knows about the personality of the speaker and his intent in producing the speech act. Of course this speaker is inferred--we cannot read minds--but this speaker is assumed to be a real person. Sometimes the implied speaker and the real speaker differ, sometimes they do not. They differ not only in the case of irony and lie, but also in the case of incompatence: "I know what you mean, even though it's not what you said."

In literature--fiction, to be more precise--we add a narrator. The narrator tells the story as true, while the author does not. That's why we need the concept of narrator even in 3rd person. But why do we need to add the concept of an implied author who is neither the narrator not the real author? Is the implied author specific to literature? To fiction? Do we need him in a biography of Napoleon?

I said above we need an implied speaker in ordinary language to distinguish lie from sincere language and irony from literal language. It would seem then that we need him in fiction too, since such ways of speaking do occur in novels. But it seems to me that there is no need to add an implied author: irony and lies and unreliability can be attributed to the narrator. But narrator's irony can be transferred to author when narrator is not an individuated human being. So my model of what the reader needs to imagine goes like this:

1 Author(what author means)--2 Narrator (what narrator means)--3 Implied narrator (what narrator says literally), with 1 and 2 collapsing in non-fiction, and 2 and 3 collapsing in straighforward expression.

The concept of imnplied author would only be useful if it were potentially distinct from real author AND the reader would be able to judge the difference, but since advocates of the implied author forbid attributing any belief and intent to the real author, the notion becomes totally non-operational.

I guess my main gripe about much of what is done in narratology is that it is trying to complicate rather than simplify things and does not adhere to the principle of Ockham's razor. The implied author, to me, is a hedge that critics use to avoid committig themselves to saying anything about the authoir. And yet, critical literature is full of "Austen tells us that", "Sartre teaches us that," etc. Is there something to be gained by outlawing these expressions?

The whole discussion of the number of implied authors in film takes the theory to its absurd limits! Will we some day have multiple unreliable implied authors in painting?

Cheers

Marie-Laure

Dear Marie-Laure,

I hope you've had a nice trip. And thanks for answering in such detail to my ruminations: if you don't mind an additional spell of intellectual ping-pong, I'll answer back between the lines:

> Dear Jose,

> Back from a short trip, this explains why I haven't posted on the list. A few thoughts on the implied author: if the implied author of "A Modest Proposal" is NOT the one who advocates Cannibalism, as I thing Booth would say, what are we going to call the one who advocates cannibalism? For surely they should be differentiated. But if we do differentiate them, we add one more entity to that already cumbersome model of author-implied author-??-narrator.

Well, as I take it, we would call the one who advocates cannibalism "the narrator" or perhaps "the speaker" since this is not a narrative proper. And the one who doesn't, the implied author. Whom we know as Swift, or rather, Swift-in-his-text. Should Swift have advocated cannibalism in his final madness, that would be a matter relevant to the biographical author, not to the implied author of this text. Anyway, we are constructing, perhaps, a simplified model of Swift's irony here, for the sake of the argument, because the actual Modest Proposal, or Gulliver, or any other text by Swift, exhibit ambiguities and imperceptible transitions between voices which would need to be analysed in greater detail.

> My stance of this is as follows: ALL utterances--whether literary or not, fictional or not--have an implied speaker and a real speaker. The implied speaker is the one who fulfills the felicity conditions of the speech act taken literally. It is the speaker in Swift who advocates cannibalism. This implied speaker never lies, never uses irony or sarcasm. Then there is the real speaker, constructed by the hearer on the basis of the content of the utterance, the context, what he knows about the personality of the speaker and his intent in producing the speech act. Of course this speaker is inferred--we cannot read minds--but this speaker is assumed to be a real person. Sometimes the implied speaker and the real speaker differ, sometimes they do not. They differ not only in the case of irony and lie, but also in the case of incompatence: "I know what you mean, even though it's not what you said."

I agree, of course, though there are some terminological problems. In your account here, the "implied speaker" of an ironic utterance is not using irony (Swift's cannibal), while the "real speaker" of an ironic utterance is the ironist (Swift). The problem is that (as you stated before concerning the differences with Booth's usage) your "implied" refers to the level would call the (unreliable) narrator, and your "real" refers to Booth's implied plus real author. This is understandable, because any speaker/writer is "implied" in his text: the cannibal in his cannibalistic text, and the ironist in his ironic text, when read as irony.

> In literature--fiction, to be more precise--we add a narrator. The narrator tells the story as true, while the author does not. That's why we need the concept of narrator even in 3rd person. But why do we need to add the concept of an implied author who is neither the narrator not the real author? Is the implied author specific to literature? To fiction? Do we need him in a biography of Napoleon?

Not specific to literature; this is a matter of general communication, especially writing. In a biography of Napoleon? Well... perhaps. It depends on what you are trying to do. If you are comparing the author-in-the-text (implied author) to another expression or text of the same author, you might need to distinguish the author you construct on the basis of this text from the one you construct on the basis of his journalistic articles, etc.

> I said above we need an implied speaker in ordinary language to distinguish lie from sincere language and irony from literal language. It would seem then that we need him in fiction too, since such ways of speaking do occur in novels. But it seems to me that there is no need to add an implied author: irony and lies and unreliability can be attributed to the narrator.

OK, fictional narrators can do anything authors can do (since fictional narrative may be motivated as fictional authorship). But in order to interpret unreliability, you need to contrast the unreliable narrator (e.g. Jason in The Sound and the Fury) with someone who holds a reliable moral (intellectual, etc.) position: and that is the author. The author-in-the-text, as you construct his position, that is, the implied author. ("Faulkner", for Booth). If you're a good reader, you don't read Jason's text as being endorsed by the author, you read an implied evaluation between the lines. And insofar as that is a textual, implied, constructed position, we're speaking of an implied author, irrespective of our knowledge of other Faulkner texts or anything about Faulkner as a person ("the real author") apart from this novel.

> But narrator's irony can be transferred to author when narrator is not an individuated human being. So my model of what the reader needs to imagine goes like this:

> 1 Author(what author means)--2 Narrator (what narrator means)--3 Implied narrator (what narrator says literally), with 1 and 2 collapsing in non-fiction, and 2 and 3 collapsing in straighforward expression.

> The concept of imnplied author would only be useful if it were potentially distinct from real author AND the reader would be able to judge the difference, but since advocates of the implied author forbid attributing any belief and intent to the real author, the notion becomes totally non-operational.

But it is potentially distinct from the implied author, there are many possible examples in which it is not only operational, but necessary. Unwanted juvenilia. Recantations. Conversions. Etc.—to take just one possible line of difference. I don't know about "advocates of the implied author", but Booth, in Critical Understanding, often contrasts the implied author in a given work and the author in other works or communicative interactions. And me too!

> I guess my main gripe about much of what is done in narratology is that it is trying to complicate rather than simplify things and does not adhere to the principle of Ockham's razor.

But sometimes we need to multiply the entities in order to deal with a complex case, because in verbal art, art consists in a multiplication of such levels of utterance. So, I'm all for simplification, but where it is advisable, or possible, one should not simplify one's toolkit so that an essential tool is missing. BTW, I read the other day an interesting paper (almost a hundred years old) on Ockham's razor: I'm enclosing it in case you feel curious about it.

> The implied author, to me, is a hedge that critics use to avoid committig themselves to saying anything about the authoir. And yet, critical literature is full of "Austen tells us that", "Sartre teaches us that," etc. Is there something to be gained by outlawing these expressions?

I'm not at all for outlawing. Rather, we need to speak of the author as a figure in the text, the "implied author" and as someone who has designed (not always in a fully conscious or controlled way) the appearance and features of such a figure, and that would be "the author". The one who is bored to death with writing potboilers is also the author, not the implied author!

> The whole discussion of the number of implied authors in film takes the theory to its absurd limits! Will we some day have multiple unreliable implied authors in painting?

Hahah! well you never know! That's beyond myself for the moment, though. As to film, yesterday I read at the end of the credits in a theater, "Columbia Pictures is the Author of this film"... so yet one more candidate, and an authoritative one! Cheers! JOSE ANGEL

Anyway, we both stood our ground in the end.

Thus far narrativeness or narrativity... Now for literariness. Fatemeh Nemati writes:

> Dear members of Narrative group

> Narratives told everyday everywhere by everyone are much similar to literaray narratives. It seems that they follow the same principle of representing the world. What makes the difference between a literary and a non-literary narrative if they are alike in every aspects of representing experiences of the real world? What happens to a narrative when it is branded as literary in contrast to non-literary? Do they differ in the meaning they convey or the way they convey it? Is it fictionality that promotes a narrative to the status of being literary rather than non-literary? Is it a magical transformation? How do you recognize that this narrative is literary rather than non-literary? are there yardsticks to measure it or are we again to depend on our intuition? What is the elixir that causes a narrative to transcend beyond the mundane reality, to enter the world of literature? I'm so perplexed that i feel i will die in the maze if nobody comes to my help. Kind regards

> Nemati

Dear Nemati:

I agree there is much common ground, certainly, between everyday conversational storytelling and literary narratives. In the last analysis, literary narrative derives from such oral stories. So there is in fact a continuum between literary and non-literary narratives. And what makes a story more or less literary (I would like to emphasize the "more or less", because it is not a matter of either/or, but a question of degree, context, etc.), what makes a story more or less literary is in part the use it is put to, and in part whether it shares a number of characteristics, none of which is in itself determinant. For instance, you mention fictionality, and well, yes, there is much common ground between literature and fiction, and a fictional conversational story would rate in principle as more "literary" than an instrumental one (conveying practical information, for instance). There are many other such parameters: whether a story has a status as a cultural icon or reference point (e.g. classical historical works, which nevertheless are supposed to be "factual"). Whether we are focusing on the story for the sake of narrative pleasure, and not for practical information. Whether the story uses language in a distinct, creative, rhetorically effective way. Whether it is tellable, repeatable... Whether it is written using literary conventions, and published as "literature". Etc. As I say, I see this as a number of criss-crossing parameters, none of which determines whether a story is to count as literary. The context of use is all-important. And the story's story: some stories are born literary, some become literary, and some have literariness thrown upon them!

Robert Scholes wrote:

The literary vs. non-literary distinction has nothing to do with fictional vs. real. It has to do with highbrow narrative vs. low-brow narrative, the stuff in "little" magazines vs. the stuff in "pulps," for example.

The distinction was used to distinguished "quality" fiction from cheap, popular stuff. Personally, I rejected that distinction long ago.

Bob Scholes

...and I reply:

There are many different notions as to what literature is, and many different contexts in which literature is distinguished from non-literature, so there is no way a clear-cut definition of literature can possibly be provided, from a "bird's eye view" of cultural phenomena. That doesn't mean that in a given context, or for one given person, the line between literature and non-literature may be quite sharply drawn; my point is that this would be just one context, or one notion, among many. That's why we need a fuzzy definition of literature according to a number of criss-crossing and grading scales.

Nonetheless, some notions are more widely shared than others, and some are more influential than others. For instance, more people would agree that "the book which inspired the film" is literature (good or bad, etc.), while "the film based on the book" is not literature (but film). And more people (more influential contexts, etc.) would agree that a highbrow, culturally valued text is literature, while a joke I happen to invent and tell my friends is not literature. Which is not to say that a given theorist may refuse to make that difference, in a given context. Or, again, many people will find it strange that Winston Churchill should be given the Nobel Prize for literature (quite apart from the quality of his style), while not many people will find it strange that Faulkner should be given the Nobel Prize for literature (whether they like his fiction or not), because "creative fictional writing" tends to be associated with literature in the minds of many people, while "history" tends to be put on another shelf by many people, libraries, bookstores, etc. I think it is useful to keep in mind which are the usual senses given to words, and uses given to books, whatever our theoretical preferences may be. Our theoretical proposals will have to intervene and make sense in (or try to change) that "real" cultural world, after all...

The list goes on...

Sin Complejos 25/2/17: El documental francés sobre el 11-M

Pino, Luis del. "Sin

Complejos: El documental francés del 11-M." EsRadio 25 Feb. 2017.*

2018

—oOo—

Retropost #1476 (26 de febrero de 2007): Desaparece Kira

Este fin de semana, en Biescas, se ha perdido Kira, la perra de mis sobrinitas Cris y Virginia. Es una cocker spaniel color miel, talmente como la de la foto que he puesto. La dejaron atada a la puerta de casa media hora, y ha desaparecido. Algo totalmente fuera de sus costumbres (es animal de costumbres) así que seguramente se la ha llevado alguien. Igual con buena intención y todo, creyendo que estaba abandonada, sobre todo si se ha soltado… aunque por Biescas casi todos los perros andan sueltos. Lo más probable es que la hayan robado. Con la de gente que está por el pueblo de paso los fines de semana… Muy tristes se han quedado Cris y Virginia, sobre todo porque no saben qué vida va a tener a partir de ahora Kira. Creo que no la volveremos a ver nunca. La vida de Kira, segunda parte, acaba de empezar. Ojala le vaya bien, pobrecilla perra, que es más inocente que ella sola. Y no van con ella esas historias de perros que se orientan y vuelven a casa recorriendo cien kilómetros.

Este fin de semana, en Biescas, se ha perdido Kira, la perra de mis sobrinitas Cris y Virginia. Es una cocker spaniel color miel, talmente como la de la foto que he puesto. La dejaron atada a la puerta de casa media hora, y ha desaparecido. Algo totalmente fuera de sus costumbres (es animal de costumbres) así que seguramente se la ha llevado alguien. Igual con buena intención y todo, creyendo que estaba abandonada, sobre todo si se ha soltado… aunque por Biescas casi todos los perros andan sueltos. Lo más probable es que la hayan robado. Con la de gente que está por el pueblo de paso los fines de semana… Muy tristes se han quedado Cris y Virginia, sobre todo porque no saben qué vida va a tener a partir de ahora Kira. Creo que no la volveremos a ver nunca. La vida de Kira, segunda parte, acaba de empezar. Ojala le vaya bien, pobrecilla perra, que es más inocente que ella sola. Y no van con ella esas historias de perros que se orientan y vuelven a casa recorriendo cien kilómetros.PS. Apareció Kira, por fin—muerta, en el sótano de un solar en construcción. Muy posiblemente tirada allí por algún malintencionado cainita.

—oOo—

sábado, 25 de febrero de 2017

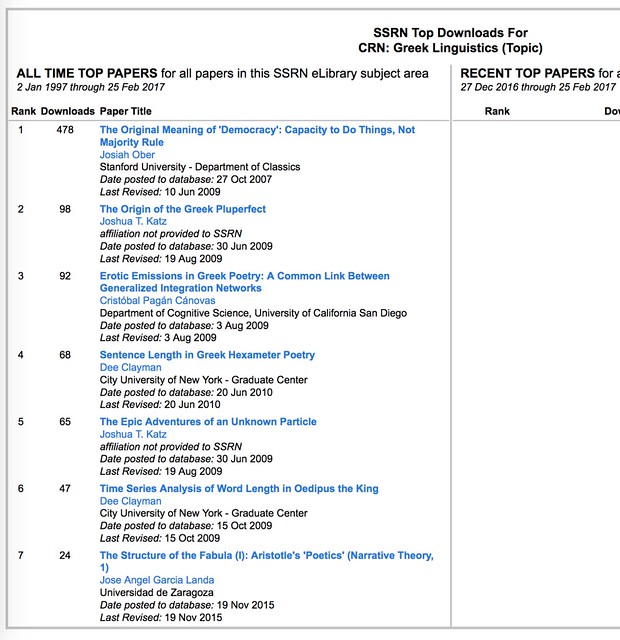

Top Ten in Greek Linguistics

|

|

Dear Jose Angel Garcia Landa:

Your paper, "THE STRUCTURE OF THE FABULA (I): ARISTOTLE'S 'POETICS' (NARRATIVE THEORY, 1)", was recently listed on SSRN's Top Ten download list for: CRN: Greek Linguistics (Topic).

As of 25 February 2017, your paper has been downloaded 24 times. You may view the abstract and download statistics at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=

Top Ten Lists are updated on a daily basis. Click the following link(s) to view the Top Ten list for:

CRN: Greek Linguistics (Topic) Top Ten.

Click the following link(s) to view all the papers in:

CRN: Greek Linguistics (Topic) All Papers.

To view SSRN's Top Ten lists for any network, subnetwork, eJournal or topic on the Browse list (reachable through the following link: http://www.ssrn.com/Browse), click the "i" button to the right of the name, and then select the "Top Downloaded" link in the popup window.

Your paper may be included in future Top Ten lists for other networks or eJournals. If so, you will receive additional notices at that time.

—oOo—

Retropost #1485 (25 de febrero de 2007): Paseo al Pibo

Domingo 25 de febrero de 2007

Paseo al Pibo

Llegamos a Biescas con la villa enmarcada por un arco iris espectacular, lástima de cámara de fotos. Luego ha habido de todo: tanto lluvia abundante, como día de viento soleado. Por variedad no quedará el pueblo. Ahora que los críos ni se han enterado: no hay quien los despegue del ordenador, para ellos Biescas se está convirtiendo en una sesión de videojuegos. Eso de pasear por el campo con ellos no va; sólo a la fuerza. Lo mismo decía mi padre de mí en 1970... aunque mi droga era otra, los libros y dibujos. Hoy me he ido de paseo con él por Arratiecho; ayer, por simetría, me llevé a Ivo, capturado a la fuerza, por el barranco de enfrente, Arás. Fuimos por la carretera vieja, subimos bordeando el barranco hasta enfrente de las Señoritas, y nos paseamos por la presa más alta que vimos, qué vértigo para el Pibo. Tuvo el honor de escribir su nombre con una piedra junto al de otros excursionistas. Luego bajamos por la carretera de Aso, y llegamos ya de noche cerrada al pueblo. El crío aguantó bien, pero fue la excursión más larga de su vida, decía: iba largando todo el rato, produciendo ideas con la cabecilla sin parar.

"Papá, hemos batido tres récords. El de longitud, el de rato, y el de altura. Te has pasado cinco pueblos, me parece. Mira: desde aquí se ven, uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco. Cinco auténticos pueblos. Se van a preocupar por nosotros, nos llamarán por teléfono móvil. Vaya, está apagado. Entonces oirán 'piii-piii-piii. Y una voz. El teléfono está apagado. Puede usted participar en una lotería. Si desea participar en nuestra lotería, marque...' Cuelgo, clac. O mejor: cerbatana. Dardo venenoso por el... por el abricular. Va por el cable el dardo. Zas. Le da al señor en la oreja—¿eeeh? Papá. ¿Tú crees que mi nombre durará mucho en la piedra? Igual no saben que soy yo. El otro día escribí mi nombre con la bici. Mira: voy deprisa, y frenazo. I. Luego vuelvo, y frenazo, frenazo. Uve. Luego cogiendo carrerilla un frenazo torcido, una cé, y otra cé al revés. Mi nombre con la bici. ¿Puedo poner aquí una marca, la del récord de altura? Qué cansado estoy. Estos árboles tienen mucho musgo: ¿puedo quedarme a dormir en un árbol con musgo? En bici bajaría a cien por hora hasta el pueblo. Como una piedra de Indiana Jones. A cien o a cien mil millones. ¿Te puedes tirar en bici por la vía del tubo? Yo quiero subir hasta arriba de la vía a ver la vagoneta. Dice Álvaro que está oxidada, pero que está. ¿Iremos un día a ver la vagoneta? ¿Nos tiraremos en la vagoneta? ¡Aaaaaah! Explosión. Papá. ¿Me puedes decir cuál es el lado positivo de este paseo?"

Y vuelta para Zaragoza. Por lo menos han visto a una buena colección de primos, qué digo primos, primas: Lizara, Blanca, Víctor, Linza, Elsa, Virginia, Cristina... y Álvaro se ha disfrazado de preso para carnaval; Lizara de Eduardo Manostijeras—ahora le ha dado por Tim Burton, y vieron todos La novia cadáver. Los pequeños se olvidaron de sus disfraces respectivos, de cebra y de jirafa, pero bueno, no parece que los hayan echado en falta. (Creo que es porque no eran de jirafo y cebro, que están en la edad sensible). Ahora los voy a extraer del baño, que igual se me arrugan.

viernes, 24 de febrero de 2017

Adaptaciones noruegas de Alicia

Me citan en Oslo, en esta tesis de máster sobre adaptaciones noruegas de Alicia en el País de las Maravillas. Bueno, yo escribí sobre adaptaciones de Shakespeare, pero todo circula y fluye.

Engdal, Tuva Maria. Alice

i Norge: En analyse av tre norske adaptasjoner av Alice's Adventures in

Wonderland. MA diss. Universiteit i Oslo, 2016. Online at UiO Duo Viternarkiv.*

Aquí un resumen en noruego:

Un documental independiente sobre el 11-M

El documental del cineasta izquierdista francés Cyrille Martin, sobre los atentados del 11-M. Se titula Un nuevo Dreyfus: Jamal Zougam, ¿Chivo expiatorio del 11-M?

Su interpretación desautoriza (una vez más) la versión oficial, y coincide sustancialmente con las investigaciones de Fernando Múgica, de Luis del Pino y otros que defienden el montaje de la conspiración, del encubrimiento oficial, y de la falsificación de pruebas. Quién organizó realmente el atentado, sigue siendo un misterio. Quién tiene interés en ocultarlo y en negarlo, está más claro, y es la pista que se deberá seguir si un día algún gobierno decide investigar este asunto, en lugar de seguir encubriéndolo.

Su interpretación desautoriza (una vez más) la versión oficial, y coincide sustancialmente con las investigaciones de Fernando Múgica, de Luis del Pino y otros que defienden el montaje de la conspiración, del encubrimiento oficial, y de la falsificación de pruebas. Quién organizó realmente el atentado, sigue siendo un misterio. Quién tiene interés en ocultarlo y en negarlo, está más claro, y es la pista que se deberá seguir si un día algún gobierno decide investigar este asunto, en lugar de seguir encubriéndolo.

Retropost #1484 (24 de febrero de 2007): Pausa de gremios

Llevamos dos semanas con la casa invadida de gremios, y pronto serán

tres. Estamos reformando un baño para adaptarlo al abuelo, que tiene

noventa y no sé cuantos años y se pega unos castañazos de aúpa entrando y

saliendo de la bañera. Total que desde la punta la mañana los tenemos

en casa, obreros de aquí para allá y los habitantes medio zombis aún en

pijama tropezando con los ladrillos y las hormigoneras. Y la casa con un

palmo de polvo, pero ahora ya empieza a volver a su ser. Lástima no

haber plantado hierba por todo. Aunque lo peor viene ahora, claro:

factura millonaria para los reformeros.... Lo de la reforma a coste cero

sólo se lleva en la Universidad.

Así que hoy que han decidido tomarse una pausa los workmen (la mitad rumanos o búlgaros, creo), nos subimos a Biescas. Parece que el día acompaña, además. Pues cierro y a ver si recojo antes de salir todas las cervezas de una pizza party que hicimos con un grupete de amigos ayer, justo dio tiempo de que saliesen los gremios y entrasen ellos: veintitrés-efe, cumpleaños de Rosa era, y allí estuvimos celebrando, ya puestos a cumplir años...

Oye, la ópera dicen que cumple hoy cuatrocientos años. Felicidades también.

Así que hoy que han decidido tomarse una pausa los workmen (la mitad rumanos o búlgaros, creo), nos subimos a Biescas. Parece que el día acompaña, además. Pues cierro y a ver si recojo antes de salir todas las cervezas de una pizza party que hicimos con un grupete de amigos ayer, justo dio tiempo de que saliesen los gremios y entrasen ellos: veintitrés-efe, cumpleaños de Rosa era, y allí estuvimos celebrando, ya puestos a cumplir años...