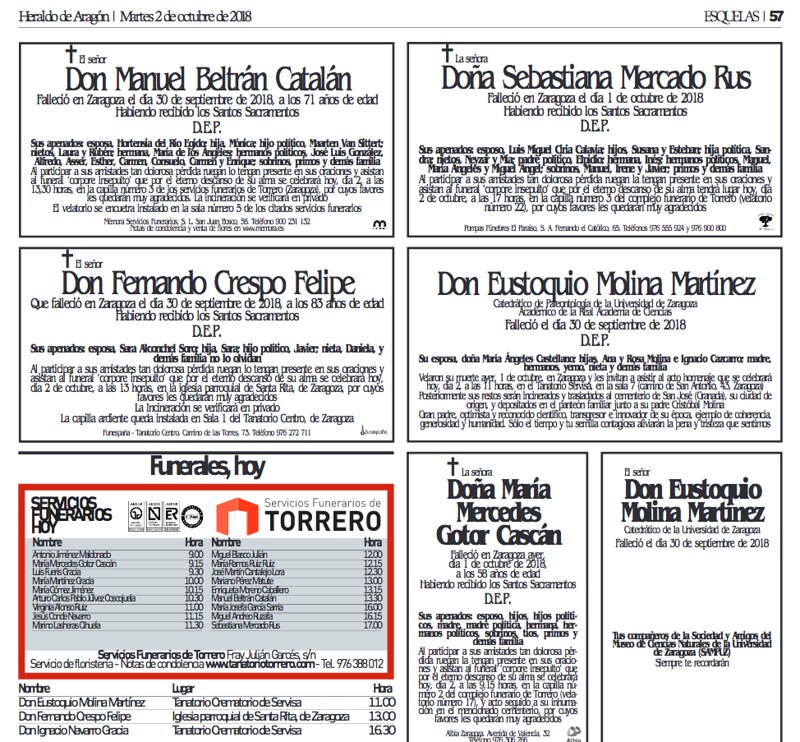

Hoy hemos sabido que ya nos habíamos despedido para siempre, sin saberlo, de nuestro querido amigo Eustoquio Molina. Le echaremos en falta cada día. Cada día es ese día en el que nunca sabes si has visto a alguien por última vez. A esas personas con quienes te tratas a diario cada día, un día más que de repente es el último día para cualquiera de nosotros.

domingo, 30 de septiembre de 2018

Adiós a Eustoquio Molina

Las cloacas de Villarejo

Retropost (30 de septiembre de 2008): Interviú

Sale hoy en el blog POE una entrevista que me hacen, relativa a la carrera y disciplina de Filología Inglesa: será la primera de una serie de entrevistas con otros profesores. Iré poniendo enlaces a ellas, pero la mía la pongo entera a continuación:

Entrevista al profesor José Ángel García Landa

Comenzamos una serie de entrevistas a profesores de Filología Inglesa de diversas asignaturas y universidades y lo hacemos con José Ángel García Landa de la Universidad de Zaragoza.

1. ¿Qué asignaturas imparte?

- Shakespeare (quinto curso de Filología Inglesa)

- Comentario de Textos literarios Ingleses (tercer curso de Filología Inglesa)

Solía impartir además un curso de doctorado, pero últimamente se instaurado una singular normativa en mi departamento que me inhabilita para impartir postgrado.

2. ¿Cuántos años lleva en la enseñanza universitaria?

Desde 1987. Pongamos veinte.

3. ¿Cómo definiría usted 'filología'?

Me gusta la definición del Diccionario de Autoridades: "PHILOLOGIA. s.f. Ciencia compuesta y adornada de la Gramática, Rhetórica, Historia, Poesía, Antigüedades, Interpretación de Autores, y generalmente de la Crítica, con especulación general de todas las demás Ciencias."

Este vaporoso estudio humanístico sin embargo resulta poco adaptable a las exigencias de una titulación universitaria moderna. Es más manejable la definición de Filología como el estudio en profundidad de una lengua en relación con su literatura y (más en el trasfondo) con la historia y cultura de los pueblos que la hablan.

¿En qué ha cambiado, si es que lo ha hecho, el significado del término desdeque usted empezó a estudiar hasta el momento actual?

El significado no ha cambiado, pero tiende a arrinconarse como plan de estudios académico en favor de otras denominaciones como "Estudios ingleses" (franceses, alemanes, etc.), "Traducción", "Lingüística (inglesa, francesa, etc.)" Filología ya no gusta a mi profesión, les suena a decimonónico, a Historia de la Lengua, a Anglosajón. Hay aquí una cierta neurosis de no perder la comba de los tiempos, y lleva a veces a curiosas declaraciones de filólogos, en un departamento de filología, diciendo que la Filología es cosa de otros tiempos.

¿Cuál sería el futuro inmediato de las filologías?

No sé otras, pero la Filología Inglesa ha decidido mayoritariamente remozarse como "Estudios ingleses" a instancias de los acuerdos adoptados a través de la asociación nacional de anglistas, AEDEAN (Asociación de Estudios Ingleses y Norteamericanos). Cada universidad puede, sin embargo, diseñar sus propios grados, y veremos también grados (y másteres) en lingüística, en traducción, etc. En filología, creo que no. En mi despacho tengo una estatuilla de un Stegosaurus, y encima del cartelito de su peana he pegado un letrero que pone "Philologia". No es lo que yo pienso, obviamente, pero es lo que piensa y ha decidido hacer la profesión en pleno.

¿Hacia dónde se dirige la disciplina?

El nombre, hacia su extinción, supongo. Los estudios, hacia una reordenación según líneas más orientadas a una disociación entre estudios lingüisticos teóricos, traducción, y estudios culturales (la literatura pierde peso y se engloba aquí). La conciencia del espacio común o de interacción entre estas disciplinas no se ha perdido totalmente, pero no interesa mucho una titulación que ponga énfasis en ello, ni que se llame"Filología".

4. ¿Qué criterios sigue usted a la hora de elaborar el contenido de las asignaturas? ¿Cómo elige los autores y obras que forman parte del programa?

Dos criterios, de los cuales el primero tiene mayor peso: a) Lo que "se espera" en un típico programa de estudios universitario de literatura, crítica literaria, o lo que sea la asignatura. b) Con menor peso: mis gustos o preferencias personales, que siempre orientan la elección de contenido, pero no conviene que pasen a ser el librillo que tienen que estudiar los sufridos estudiantes.

5. ¿Qué ventajas e inconvenientes ve a la reforma de los estudios de Filología Inglesa?

Ventajas: una mayor adaptación a las necesidades del mercado de trabajo. Quizá un mayor reconocimiento de las otras vías existentes hoy en día para una formación en inglés. Inconvenientes: la pérdida de identidad de la disciplina como tal, y del trabajo más propio de ella, en favor de estudios más estandarizados de secretariado multilingüe, traducción, lingüística o "estudios culturales". He escrito bastante en mi blog sobre los avatares e incidencias de esta reforma, incluida la amenaza (que la hubo) de suprimir la titulación de Filología Inglesa o Estudios Ingleses http://garciala.blogia.com/temas/filologia-inglesa.php

6. ¿Qué le recomendaría a alguien que se plantea matricularse en Filología Inglesa?

Que escoja una buena universidad. Y que tenga claras sus perspectivas de carrera: quizá para ser profesor de enseñanza secundaria le valga más un título de máster específico y quizá, para ser traductor, le sirva más una titulación en traducción. Son tiempos de crisis e incertidumbre en la filología, y se nota en el alumnado. Muy distinto es ahora de cuando yo terminé la carrera, y estudiar Filología Inglesa era una garantía de colocación.

—Bueno bueno... tan perdida está la noción sobre de qué va esto de la Filología Inglesa, que el otro día tuve que hacer la observación en nuestra Comisión de Postgrado de que tal como está planteado ahora nuestro postgrado en Estudios Ingleses, puede salir doctorado alguien que no sepa inglés. Se reconoció que era un pequeño problema en el que no se había caído... pero que bah. Es un caso extremo, pero a los estudiantes se les pide que salgan formados en el tema de su investigación en concreto, y no en "filología inglesa" en general. Que un profesor universitario domine mínimamente todas las materias de la carrera, en especial las más centrales a la noción misma de Filología, es algo que está fuera del horizonte de la universidad actual, que pide "especialistas". Y en el caso de la Filología Inglesa, se piden "lingüistas" o "literatos"—nunca "filólogos".

No me extrañaría que otros profesores fuesen más optimistas que yo. Después de todo, el inglés es un idioma que no corre peligro, pase lo que pase con la Filología Inglesa.

(PS: Otras entrevistas en POE: Entrevista a la profesora Mª Angeles Escobar; Entrevista a la profesora Laura Alba Juez; Entrevista a María Magdalena García Lorenzo)

Retropost (30 de septiembre de 2008): La foule / Que nadie sepa mi sufrir

Cantada por Agnès Jaoui y Jacques Higelin. Uau. Muérete de envidia, Piaf.

PS: Hoy es el día en el que nos enteramos del secreto mejor guardado de la familia, durante muchos muchos años.... "Que nadie sepa mi sufrir", en efecto. Hablaré de esto cuando calibre bien que se puede, en algún futuro.

sábado, 29 de septiembre de 2018

Censura etarroide en Twitter

Ahora @TwitterEspana bloquea a la asociación de víctimas del terrorismo @CovitePV y a su presidenta Consuelo Ordoñez. No he oído que hayan bloqueado nunca a un terrorista como Otegui ni retirado ni en activo. O se están volviendo locos o es algo peor. https://t.co/bCHVcLaB5O— Hermann Tertsch (@hermanntertsch) 29 de septiembre de 2018

Twitter cuida, eso sí, la libertad de expresión de la antiespaña catalazi, separata y etarroide.

_______

PS. Han restaurado las cuentas ante la reacción de escándalo suscitada. Tremendo patinazo. O más que patinazo—ahí hay algún encapuchado.

Retropost (29 de septiembre de 2008: Herramientas

Ahora que es el cuarenta aniversario de 2001: Una odisea del espacio vamos a superponer tecnologías: me he acordado de este artefacto que me encontré antes del verano mientras me daba un paseo con los chavales por cerca de la desembocadura del Gállego. Bueno, en realidad creo que lo encontró Pibo, y nos llamó la atención inmediatamente.

Para mí que es un hacha de piedra pulimentada, posiblemente de muchos miles de años de antigüedad, y no un producto de la casualidad. No se me ocurre una tecnología más reciente que necesitase artefactos de piedra de esta forma y acabado, aunque claro, igual estoy equivocado.

Si la agarras, es ergonómica—aunque se nota que está hecha para una mano más pequeña que la mía. Pigmeos ibéricos, quizá...

viernes, 28 de septiembre de 2018

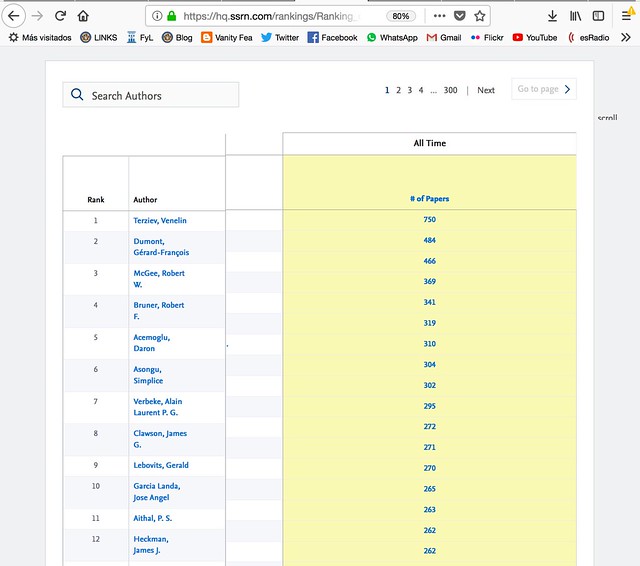

Posicionamiento 10

Retropost (27 de septiembre de 2008): Tecnologías de sincronización

Estoy leyéndome el muy interesante libro de Julio Iglesias La dimensión social del tiempo (Madrid: Real Academia de Ciencias Morales y Políticas, 2005)—otra "historia del tiempo" que si bien tiene algunos puntos de contacto con la de Hawking, se refiere más bien a la organización, uso y conceptualización social del tiempo. Y atiende sobre todo a las transformaciones del tiempo en la modernidad, en la ciudad, y en el contexto globalizado que vivimos, así como a los efectos de la sociedad de la información en la reorganización de la experiencia temporal. Un índice:

I. Del tiempo y su ordenación: los calendarios.

II. El tiempo en el pasado.

III. La conciencia moderna del tiempo.

IV. El tiempo del tiempo. (Einstein o la relatividad del tiempo; Piaget y el tiempo en la infancia; El reloj biológico; Políticas del tiempo y ahorro económico; La política de reducción del tiempo de trabajo; La necesidad de medidas temporales muy breves; La sociedad del instante en la sociedad de la información).

V. Tiempo y familia.

VI. Tiempo y trabajo.

VII. De la política y el tiempo.

VIII. El tiempo en perspectiva: pasado, presente y futuro.

Epílogo: La actualidad del tiempo.

Sigue un discurso de contestación del académico (oximorónicamente llamado) Salustiano del Campo Urbano. (Mis chavales siempre me recuerdan la gran frase clásica que resume nuestra historia: "Antes todo esto era campo").

Durante mucho tiempo la sociedad vivió "de espaldas al tiempo", o más bien en un tiempo común y natural regulado por los ciclos del día, la noche y las estaciones. La apropiación y manipulación social del tiempo puede seguirse a través de los instrumentos de medición y sincronización de actividades que se van desarrollando: calendarios, relojes, horarios de trabajo, y recientemente, en una apoteosis de milimetración temporal, los sistemas informáticos que detallan el tiempo de cada transacción social. El desarrollo de la medición y sincronización temporal va unido al desarrollo del capitalismo, local primero y global después, y de su concepción del trabajo y de las actividades como algo medible, a medida que pasamos del campo a la urbe. Una concepción que deriva de Simmel.

Son excelentes las relaciones que establece Iglesias entre el desarrollo de procesos económicos y sociales a gran escala y las manifestaciones locales de las nuevas concepciones temporales. Por ejemplo, el reloj como arquetípico regalo burgués simboliza la regulación temporal del matrimonio. O el libro de Julio Verne La vuelta al mundo en 80 días, con su argumento cronométrico, es un síntoma de una nueva concepción global de las comunicaciones—Y todo efecto de la globalización o sincronización universal, y de la división (sincronizada) del trabajo. Desde los cambios en los patrones de ocio a las modalidades de horarios laborales y de negociación sindical, o el desarrollo de planes de estudio con asignaturas optativas, todo logra hilarlo el autor en un razonamiento magistral y panorámico.

Los blogs y foros, se me ocurre, son un caso no nombrado por Julio Iglesias, pero que ciertamente es paradigmático de esta universalización del tiempo contemporánea. Ningún texto antes ha llevado un registro temporal tan estricto (y automatizado) de su difusión y de sus comentarios, y se materializa en ellos (así como en la telefonía digital y en otros fenómenos informáticos) la apropiación del tiempo a la vez a escala milimétrica y global. También son un síntoma de lo que señala Iglesias: el avance de la regulación y medición temporal hacia esferas de la intimidad y de la privacidad antes ajenas a esta sincronización universal del tiempo.

En el ordenador puedes perder la noción del tiempo, pero sin embargo estás registrado por toda una serie de protocolos de control y de medición que registran tu actividad. Tienes el reloj delante, en una esquina de la pantalla, permanentemente, pero más allá de eso, estás trabajando dentro del reloj. Eres controlable, te registras a una hora, sales a otra, hasta tus clics quedan ubicados en un espacio-tiempo cibernético, en el que tu trayectoria, su velocidad y sus reposos, quedan recogidos en un registro temporal que además es inmediatamente procesable, para extraer estadísticas e implementar acciones correctivas a través del mismo aparato. Esto en cuanto el teletrabajo, o más generalmente el trabajo por ordenador, se implanta. Las consecuencias que extrae Iglesias de este potente cronómetro que es el ordenador me parecen insuficientes. Con los ordenadores no habrá teletrabajo: estaremos más bien inmersos en el espacio de trabajo en todo momento, estemos donde estemos; y Matrix será el resultado lógico de la sincronización universal.

Tiempo estimado de lectura de este artículo: un minuto y catorce segundos.

(PS: Más sobre sincronización, cronometría y ordenadores en este artículo de Nicholas Carr: Is Google Making Us Stupid? What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains).

jueves, 27 de septiembre de 2018

The Poetry of Spenser

XI. THE POETRY OF SPENSER

After a lapse of almost two centuries we reach the first English major poet since Chaucer. Edmund Spenser (1552-99) was born in London, and was related to the great family of his name. At Cambridge he not only wrote his earliest sonnets, but came under three profound influences. The first was his friendship with Gabriel Harvey, a powerful and controversial scholar, to whom justice has yet to be done. The second was teh refined and cultured "Puritanism", which, like that of Milton, was a revolt from coarseness and materialism in life and in religion. The third was the study of Platonic philosophy—not the Christianized neo-Platonism of the first Reformers, but the pure Platonism of the Timaeus and the Symposium. To the imagination of Spenser this proved exceedingly congenial, and confirmed him in his allegorical habit of conception and expression. His early Hymnes, the first in honour of Love, the second in honour of Beautie, though not published till 1596 (Foure Hymnes made by Edm. Spenser), were inspired by his first experience of love, and written in the spirit of Plato.

He was brought by Harvey into the service of the Earl of Leicester, and met Philip Sidney, whose ardent imagination and lofty spirit greatly stimulated him. After toying, under Harvey's influence, with the possibilities of using in English a system of quantitative prosody (that ignis fatuus of English poets) he began to consider the forms in which he could express himself most naturally, and he turned instinctively to the pastoral and the romance, with their stock figures, the shepherd and the knight. The pastoral, as we have seen, was a popular form, offering an abundance of models. The extent of Spenser's debt to any of these is not really important. All that matters in a poem is what it is, not what it may have come from. Upon the "XII Aeglogues proportioned to . . . the XII monethes" forming The Shepheards Calendar (1579) the impress of a creative, originating poetic genius is clearly discernible. The book was dedicated to Sidney, who praised it highly, but objected, rather pedantically, to one of its greatest charms, namely "the olde rusticke language". Sidney, a typical figure of the Renascence, disliked Spenser's archaism, not in itself, but because it was unwarranted by classical originals. This kind of criticism was to have a long run. A more serious objection would have been that the pastoral, as Spenser wrote it, was a literary exercise with little hold on life. Spenser uses all varieties of the form, amatory, moral, religious, courtly, rustic, lyric, elegiac, and shows himself at once master of an old convention and herald of a new spirit in poetry. His language was deliberately archaic. Ben Jonson said that Spenser, in affecting the obsolete, "writ no language". The answer is that Spenser used the language in which Spenser could write. Every true poet creates his own idiom. What The Shepheards Calendar clearly reveals is the arrival of a great poet-musician, who excelled all his predecessors in a sense of the capacity of the English language in which Spenser could write. Every true poet creates his own idiom. What The Shepheards Calendar clearly reveals is the arrival of a great poet-musician, who excelled all his predecessors in a sense of the capacity of the English language for harmonious combinations of sound. To turn from the flatness of [George Gascoygne's] The Steele Glas to The Shepheards Calendar is to pass fro honest and well-meant effort into a new world of absolute mastery.

From the pastoral Spenser proceeded naturally to romance. In 1580 he went to ireland as secretary to the Lord Deputy, and there at Kilcolman Castle he continued his Faerie Queene, the first three books of which were published in 1590 on his return to England. As, in any creative sense, the poem shows no progress, but is at the end what it was in the beginning, some consideration of it may be given at once. The poem, as planned in twelve books, was never completed. Spenser himself has clearly stated his own intentions in the prefatory letter addressed to Ralegh, and to this the reader is referred. Like other great poets he felt himself called to teach; and desiring to set forth a picture of a perfect knight, he chose King Arthur as hero, rather than any person of his own time. Further, he desired to glorify his own dear country and its "most royal Queen". In much of his intention he was successful, but he was not completely successful. Spenser failed because he refused to follow his natural instinct for allegory and romance, the forms that most readily released his creative powers—in The Allegory of Love (1936) C. S. Lewis traced their history from Le Roman de la Rose—but turned aside to be instructive, and, in seeking to make the allegory edifying, forgot to tell the story. But if an allegory does not survive as a stroy, it does not survive as an allegory. [John Bunyan's] The Pilgrim's Progress is, first of all, an excellent story; The Faerie Queene is not. Like every great poem, The Faerie Queene is entitled to its own imaginative life; but it must continue to be true to that life. Spenser, to use a common phrase, lets us down, when we are left wondering whether the false Duessa is a poetical character, or Theological Falsehood, or Mary Queen of Scots. He tried to do too many things at once; and, in elaborating intellectually the allegorical plot he has confused the imaginative substance of the poetic narrative. Homer, says Aristotle, tells lies as he ought; that is, he makes us believe his stories. Spenser tried to tell his lies while clinging to a disabling kind of truth; and so he does not convince his readers. Thus it is neither as an allegorist nor as a narrator that the author of The Faerie Queene holds his place. He lives as an exquisite word-painter of widely differing scenes, and as supreme poet-musician using with unrivalled skill a noble stanza of his invention, unparalleled in any other language [the Spenserian stanza].

As the years advanced, Spenser seems to have felt that his conception of chivalry had little correspondence with the facts of life. Sidney was dead, and his own hopes of preferment were frustratedd. In 1591 a volume of his collected poets was published with the significant title Complaints, including such works as Tthe Ruines of Time, The Teares of the Muses and Prosopopoia or Mother Hubbard's Tale, in which the Ape and the Fox serve to satirize the customs of the court. In 1591 he returned to his exile in Ireland, and there, in the form of an allegorical pastoral, called Colin Clout Come Home Againe (1595), he gave expression to his views about the general state of manners and poetry In his Prothalamion, and still more, in his Epithalamion, he carries the lyrical style, first attempted in The Shepheards Calendar, to an unequalled height of harmony, splendour and enthusiasm. In 1595, he again came over to England, bringing with him the second part of The Faerie Queene, which was licensed for publication in January 1595-6. Finding still no place at court, he returned to Ireland in 1597; but, in a rising, Kilcolman Castle was taken and burned, and ad Spenser barely escaped with his life. His spirit was broken, and after suffering the afflictions of poverty, he died in January 1599. His posthumous prose dialogue, A Veue of the Present State of Ireland, written in 1596, is discussed in a later chapter. Spenser is the poets' poet, and his greatness cannot be diminished by the jeers of the tough-minded who find his poetic music and his poetic virtue too delicate for their manly taste.

XII. THE ELIZABETHAN SONNET

The sonnet, which was the invention of thirteenth-century Italy, was slow in winning the favour of English poets. Neither the word nor the thing reached England until the sixteenth century, when, as we have seen, the first English sonnets were written, in imitation of the Italian, by Wyatt and Surrey. But these primary efforts set no fashion. The Elizabethan sequences came long after the gentle effusion of Tottel's poets, and were not influenced by them. But when the writing of sonnets began in earnest it soon became a fashionable literary habit and no poetic aspirant between 1590 and 1600 failed to try his skill in this form. The results are not inspiring. Sidney, Spenser and Shakespeare alone achieved substantial success; and their sonnets, with some rare and isolated triumphs by Drayton, Daniel, Constable and others, are the sole enduring survivals. Tottel's Miscellany contained sixty sonnets, for the most part primitive copies of Petrarch; but though the name "sonnet" is commonly used for poems in the succeeding anthologies, the actual sonnet form is rare. Gascoigne's Certayne Notes of Instruction not only described the Elizabethan sonnet accurately, but noted the general misuse of the term. It was contemporary French rather than older Italian influence that moved the Elizabethan mind to sonnet-writing. The first inspiration came from Marot (1495-1544); though the sonnet was not naturalized in France until Ronsard (1525-85) and Du Bellay (1525-60), who, with five others, formed the constellation of poets called La Pléiade, deliberately resolved to adapt to the French language the finest fruit of foreign literature. Philippe Desportes (1546-1606), a less important poet, was specially admired and imitated by the Elizabethans.

Spenser is the true father of the Elizabethan sonnet. He first appeared as a poet with the twenty-six youthful sonnets of 1569. His indebtedness to Du Bellay is declared in the title of one group of sonnets. The Visions of Bellay, and of another, The Ruines of Rome by Bellay. Another set, The Visions of Petrarch, he translates from Marot. These and the other sonnets of Spenser in Amoretti (1595) have his characteristic sweetness of versification. Spenser, it should be noted, uses the English and not the Italian form of the sonnet. Two of the sonnets in the Amoretti refer to the Platonic "Idea" of beauty which outshines any mortal embodiment. The "Idea", found also in numerous French writers, became a theme of later English sonnets, especially those of Drayton, who borrowed his very title from a sonnet-sequence by a minor French poet, Claude de Pontoux. The first Elizabethan sonneteer to make a popular reputation, however, was not Spenser, but Thomas Watson (1557-92), who was hailed as the successor of Petrarch and the English Ronsard after the appearance in 1582 of The Hekatompathia or Passionate Centurie of Love. But nearly all the hundered "Passions" are in a pleasing metre of eighteen lines (three sixes. Watson uses the norman Elizabethan form in the sixty sonnets of The Teares of Fancie, or, Love Disdained (1593). Neither these nor the "Passions" have much poetic value.

Sir Philip Sidney (1554-86), who follows Watson, is a prince among Elizabethan lyric writers and sonneteers, and, Shakespeare apart, is easily the best. The collection known as Astrophel and Stella was written between 1580-4 and though widely circulated in manuscript was not published till 1591 (piratically) and 1598 (regularly). With Sideny we come to the first real English "sonnet sequence", a collection of sonnets telling a story of love, like that of Petrarch for his Laura. The "hopeless love" of the sonnets must not be taken literally. Readers sometimes fail to distinguish between the truth of a poem and the truth of an affidavit, and are too often encouraged by critics who ought to know better. The sonnets of Shakespeare and of Sidney are as "true" as Hamlet or Arcadia; they are not required to have a different kind of truth. Sideny was indebted to foreign models, though he was much more original than his contemporaries. His sonnets are real contributions to English poetry. They have grace, ease and sincerity, and a genuine character reflecting the admirable spirit of the writer.

Of the numerous sonneteers who followed Sidney few need be mentioned. Shakespeare will be considered in his own place. Henry Constable's Diana (1592) and Thomas Lodge's Phillis (1593), all of which borrowed extensively from abroad, have each contributed something to the English anthologies. Michael Drayton's Ideas Mirrour, first printed in 1595 and steadily revised in several editions till 1619, gives us, in its final form, the one sonnet of its time worthy to be set by Shakespeare's, "Since there's no help, come let us kiss and part". Richard Barnfield's "If music and sweet poetry agree" deservedly survives. Barnabe Barnes, in Parthenophil and Parthenope (1593), is voluminous, but says little. Later, came two Scottish writers, Sir William Alexander, Earl of Stirling (1567-1640) who reaches a respectable level, and William Drummond of Hawthornden (1585-1649) whose "For the Baptist" is the one religious sonnet which has survived as a poem. With them may be mentioned Sideny's friend, that strange genius, Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke (1554-1628), whose Caelica sequence (not all sonnets) may be held to close the story. Sonneteering fell into disrepute and perished of its own insincerity. When Milton revived the true sonnet form it took a note which cannot be heard in any of the Elizabethan collections.

Retropost (27 de septiembre de 2008): L'important c'est la rose

Me las he visto y me las he deseado para dar al mundo una versión de esta canción que, sin pecar de vanidad, diría que puede compararse con la interpretación de Gilbert Bécaud.

No se me rían, que sudado tinta he. Y es que la cancioncita de marras tiene, en la versión ésta, no menos de diecisiete acordes diferentes, cuando la mayoría cumplen con tres o cuatro. A la versión que intentaba en veintidós acordes, arrenuncio.

miércoles, 26 de septiembre de 2018

From Old English to Middle English

XIX. CHANGES IN THE LANGUAGE TO THE DAYS OF CHAUCER

The three Germanic peoples—the Jutes from Jutland, the Angles from Schleswig and the Saxons from Holstein—who in the fifth and sixth centuries made themselves masters of southern Britain, spoke dialects so nearly allied that the y could have had little difficulty in understanding each other. There was no name for their common race and common language. The Britons called all the invaders Saxons; St Gregory had to call them Angles for the sake of his famous pun; but an emperor called the Anglian king of Northumbria rex Saxonum. Though Bede sometimes speaks of Angli sive Saxones, his name for the language is sermo anglicus. Alfred, a West Saxon, calls his language Englisc. Actually the Anglian name was appropriate, for the history of southern English is largely concerned with the spread of Anglian forms. When Camden used lingua Anglosaxonica for pre-Conquest English, he meant not a blend of Anglian and Saxon, but simply "English Saxon" as distinguished from "German Saxon". The term, tough misunderstood, tended to survive. The German philologist Jakob Grimm introduced the practice of dividing a language into its Old, Middle and Modern periods, and so the term Old English came into use. There is, of course, no precise point at which people ceased to speak "Old English" and began to speak "Middle English". The terms are merely philological conveniences. However, we may regard the form of language we call Middle English as having emerged about 1150, and as having ceased about 1500, when the printing press conquered the scriptorium.

Old English retained its inflectional system; but in course of time the inflections tended to be assimilated. Thus in the declension of Gothic guma, a man, there are seven distinctive forms in the eight cases of singular and plural; in the declension of Old English guma there are only three. The almost universal substitution of -es for the many Old English endings of the genitive singular and nominative and accusative plural began before the Norman Conquest; and in the fourteenth century the Engglish of educated Londoners had lost most of its Southern characteristics and had become a Midland dialect. Chaucer's plurals and genitives end in -es, the number of exceptions being hardly greater than in modern English. The dative disappeared from Midland English in the twelfth century. Southern English (Kentish and West Saxon) was much more conservative. The forms of the Old English pronouns of the third person in all dialects were very similar in pronunciation—the pairs him and heom, hire and heora, being easily sounded alike. The ambiguity was got rid of by a process very rare in the history of languages, the adoption of foreign forms. It is from the language of the invading Danes that we get such forms as they, their, them. But the older forms persisted. Chaucer used her for their and he always has hem for them. The Old English inflections of adjectives and article, and with them the grammatical genders of nouns, disappeared early in Middle English. IN these respects Orm and Chaucer are almost alike. All these changes were once generally believed to have been brought about by the Norman Conquest; but the spoken language had travelled far towards the Middle English stage before 1066. Of course the Norman occupation had influence: the new political unity and development of intercommunication tended to diffuse grammatical simplifications; but if we except such effects as the use of of instead of a genitive inflection, and the polite substitution of plural for singular in the second person, hardly any specific influence of French upon English grammar can be traced.

As we have said in an earlier page, the runic alphabet of the heathen English was superseded, under Christian influence, by the Latin alphabet of twenty-two letters, to which were added the runic letters ᚹ(called wynn); ᚦ (called thorn) and 𐑔 (called eth). The last two were used indifferently and did not represent voiced and unvoiced th. The vowels were sounded nearly as in modern Italian, except that y was like French u and æ like a in pat. The consonants had much the same sound as in modern English. The greatest change in the written language came after the conquest, and was chiefly a matter of spelling. Children had ceased to read and write English, and were taught to read and write French. When, later, a new generation tried to write English, the spelt in French fashion. The changes in pronunciation are too intrincate for summary. How different was the course of development in different parts of the country can be seen in the fact that the English pronunciation home and stone, and the Scottish hame an stane both derive from the Old English long a as in father. The "Zummerzet" pronunciation of initial f and s as v and z was common all over the south and is exactly recorded in the Kentish Ayenbite of Inwit (1340).

The Norman Conquest had a profound influence on vocabulary. A few French words came in before the Conquest; after that event the number steadily increased. Chaucer is quite wrongly accused of having "corrupted" English by introducing French words. It cannot be proved that he made use of any foreign word that had not already gained a place in the English vocabulary. Very sad is the total loss of many Old English words. In the first thirty lines of Aelfric's homily on St. Gregory, there are twenty-two words which had disappeared by the middle of the thirteenth century. The fourteenth century alliterative poets revived some of the ancient epic synonymous for "man" or "warrior" —bern, renk, wye, freke; but they didn not last.

Only a few peculiarities of dialect can be mentioned here. The use of a dialect, of course, did not indicate an inferior education. Writers emploted for literary purposes the language they actually spoke. Chaucer would not have found it easy to read the Kentish Ayenbite of Inwit and the North-western Sir Gawayne would have puzzled him. The diversity of the written language in the different parts of the country during the fourteenth century may be indicated briefly thus: they say = Kentish hy ziggeth, East Midland they seyn, West Midland hy (or thai) sayn, Northern thai sai; their names (in the same distribution) = hare nomen, hure nomen, hir names, hur namus, thair names. The ultimate triumph of the East Midland dialect was largely due to the fact that it was midland, i.e. midway beween hy ziggeth, and thai sai. The fact that Oxford and Cambridge were linguistically in this area had an influence. The London English of Chaucer and the not dissimilar Oxford English of Wyclif became, in fact, the literary language of England.

Retropost (26 de septiembre de 2008): Todos mutantes

Los feos son mutantes. Y las pelirrojas. Los monstruos de dos cabezas, que existen, son mutantes. Los gordos, mutantes gordos. Son mutantes asimismo las personas de color (negros, chinos, blancos, etc.)—y los humanos son peces mutantes.

Este retrato de una mutante fue pintado por Lavinia Fontana en la segunda mitad del siglo XVI. Es Tognina Gonsalvus, hija del igualmente peludo Petrus Gonsalvus, oriundo de Canarias pero acogido por diversas cortes europeas. Al parecer, Tognina "acabó casándose y engendró varios hijos que fueron tan peludos como ella" (271). Me ha encantado el libro de Armand-Marie Leroi Mutantes: De la variedad genética y el cuerpo humano (Anagrama, 2007), que la tiene en portada. Ahora que Stephen Jay Gould ya murió, es bueno saber que hay divulgadores científicos tan amenos como Leroi, que cita a Gould con simpatía aunque le contradice en algunos puntos. Se lo recomiendo a todos los amantes del evolucionismo, de los monstruos, y de los mutantes.

I. Mutantes. La cuestión de las mutaciones es una vía privilegiada de entrada a un tema más general del libro "la construcción del cuerpo humano" (13). Porque aunque todos somos mutantes, no somos todos igual de mutantes, y hay casos más llamativos que yo. El libro comienza con las teratologías del Renacimiento, desde el Monstruo de Rávena hasta los de Paré y Fortunio Liceti (De Monstrorvm natvra cavssis et differentiis libri duo, 1634), pasando por las reflexiones sobre la monstruosidad de Montaigne, Browne y Bacon.

Browne, en su Religio Medici (1642), es amable y admirativo con los monstruos: "en la Monstruosidad (...) hay una suerte de Belleza. La Naturaleza ha creado las partes irregulares de una manera tan ingeniosa que a veces son más extraordinarias que la estructura principal" (en Leroi, 24). Y Bacon, en su clasificación de todas las formas del conocimiento, dedicaba un capítulo especial al conocimiento de los monstruos, por las perspectivas que ofrece para el desarrollo de la ciencia: "pues una vez una naturaleza haya sido observada en sus variaciones, y la razón que las origina haya quedado clara, será materia fácil aplicar la ciencia a esa naturaleza y llevarla al punto que alcanzó mediante el azar" (27). Todo un programa para el Dr. Moreau avant la lettre, y Leroi no parece totalmente averso a esta creación programada de mutantes, aunque observa que "Con la prohibición global de clonar humanos no es probable que este experimento se lleve a cabo pronto" (317). Peor para los periodistas, y para la ciencia; mejor quizá para el pobre mutante, aunque quién sabe.

De hecho el autor duda en calificar de mutantes a un grupo determinado de personas por oposición al resto: "Decir que la secuencia de un gen concreto presenta una "mutación", o llamar "mutante" al portador de ese gen, es realizar una distinción odiosa. Es dar a entender, como mínimo, que se desvía de un ideal de perfección"(30). Aunque por supuesto también lo hace continuamente, y de hecho al final nos hace partícipes de su curiosa teoría según la cual los guapos no son mutantes—o más bien, que los feos son más mutantes que los guapos, pues la belleza consistiría en una especie de neutralidad o bajo índice de mutaciones. Un punto que es de los más cuestionables del libro, y síntoma del mal endémico de los biólogos, buscar explicaciones estrictamente biológicas a fenómenos culturales muy complejos. Conste que bien me parece que se busquen las condicionantes biologicas de los fenómenos (el cerebro masculino contra el femenino, etc.) siempre que no perdamos de vista otras dimensiones (culturales y constructivistas) de la cuestión.

Las personas comparten casi (casi) el 100% de su genoma. En el resto está la variación: y el resto puede ser varios millones de pares base, puesto que hay casi tres mil millones de ellos en el genoma humano. Las mutaciones afectan con frecuencia a "uno de los enormes segmentos del genoma humano que parecen carecer de sentido" (31). Otras son menores, y otras por fin son espectaculares. "Cada nuevo embrión cuenta con un centenar de mutaciones que sus padres no tenían"( 32). Algunos nacen con un bajo número de mutaciones nocivas, otros con muchas. En suma: "Todos somos mutantes. Pero algunos somos más mutante que otros" (33).

II. Una unión perfecta. Capítulo que trata sobre gemelos, siameses y monstruos dobles, como Ritta-Christina Parodi. Hay interesantes datos sobre las representaciones de monstruos desde tiempos antiguos, y teorías clásicas de la monstruosidad: así la querelle des monstres, la disputa sobre si la monstruosidad forma parte del plan divino, o es un accidente de ese plan. Lo que nos lleva a dos teorías distintas sobre los embriones: la preformación o la epigénesis. El desarrollo del embrión es un tema fascinante, que nos conduce a la teoría de la evolución (el primer sentido de evolución fue precisamente "desarrollo del embrión"). En los años 90, estudiando la recombinación del ADN, se llegó por fin a identificar los genes que controlan el desarrollo. Un gran paso adelante desde las teorías de Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, coleccionista de monstruos, que pretendía deducir los principios del desarrollo a partir de sus manifestaciones anómalas. Y nos cataloga Leroi las variedades de anomalías que pueden darse: gemelos unidos, personas "invertidas" (¡no homosexuales!) por situs inversus... El organizador de todo este desarrollo es el organizador, "un grupo de células mesodérmicas localizadas en un extremo de la línea primitiva del embrión", que con unos movimientos ciliares distinguen izquierda de derecha y así orientan el desarrollo del organismo hacia uno y otro lado.

III. El juicio final (de las primeras partes). Donde se trata del museo de monstruos de Amsterdam; de cíclopes y ciclopia, en mitología y en teratología renacentista. El desarrollo defectuoso del cerebro frontal y la cara afecta a 1 de cada 16.000 nacidos, y 1 de cada 200 abortos espontáneos: el mundo está lleno de cíclopes y paracíclopes. En algún sitio los guardarán—aunque otras fuentes nos dicen que muchos son asfixiados por los médicos, discretamente y sin preguntar a nadie, y clasificados como "nacidos muertos". Mejor que nadie llegue a verlos, a juzgar por las ilustraciones del libro de Leroi. Muchos de estos casos se deben a mutaciones en los genes que producen una proteína llamada "erizo sónico"—la que debía producir dos hemisferios cerebrales divididos. Otro tipo de trastornos puede producir una duplicación total o parcial de la cara—y hasta individuos con dos cabezas. Otra monstruosidad estándar es la sirenomelia, un defecto en la línea media de las extremidades posteriores. "Los morfogenes que atraviesan el embrión en desarrollo—sean proteínas o anillos de hidrocarburos—proporcionan a las células una especie de retícula de coordenadas que éstas utilizan para averiguar dónde están y qué deberían estar haciendo y ser" (93). La homeosis, fenómeno "en el que una parte del embrión en desarrollo se transforma de manera anómala en otra", dándonos por ejemplo orejas en el cuello.Y así, viendo el proceso de construcción y la manera en que es organizado por los morfogenes, y la manera en que se puede distorsionar este proceso, va ordenando Leroi distintos tipos de monstruosidades. Con el estudio de las moscas de la fruta Drosophila se halló la combinatoria informática de las proteínas que rigen el crecimiento. "La calculadora segmental es algo hermoso. Posee la económica lógica booleana de un programa de ordenador. Cada una de las proteínas codificadas por los genes homeóticos se presenta en ciertos segementos" (98). Los genes pueden crear proteínas, pero necesitan ser activados o desactivados por el ARN mensajero , "una molécula muy parecida al ADN, sólo que no es doble ni es una hélice, sino tan sólo una larga serie de nucleótidos" (99). El núcleo organizador de esta información, la homeocaja, es "la piedra de Roseta" de la genética del desarrollo, y están presentes en todo tipo de animales. La presencia y ausencia ordenada de genes Hox (numerados) regula la formación de segmentos del cuerpo—en su debido número o con anomalías. Son universales anatómicos: organizan tanto los segmentos de las moscas como de los humanos, y en el mismo orden. Aunque también hay disimilitudes, como la inversión arriba-abajo entre artrópodos y cordados que tanto intrigaba a Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Quizá pudiese explicarse con una mutación en un remoto antepasado. Pero al margen de estos genes Hox hay muchos más instrumendos de señalización: "los factores de transcripción vienen en familias, de las que lo genes homeocaja son sólo una" (105).

IV. Atrofiados (de brazos y piernas).

Aquí se tratan fenómenos como la ectrodactilia, o manos y pies en forma de pinzas de langosta; el famoso semi-mito de la tribu africana "con pies de avestruz", la aqueiropodia o atrofia de las piernas, y el violinista sin brazos Hermann Unthan. También los estragos de la talidomida... Aquí puede verse por cierto un vídeo de Tony Meléndez, admirable guitarrista sin brazos:

John Saunders estudió la manera en que las extremidades de desarrollan creciendo hacia afuera, a la manera de los brotes de las plantas, y cómo se pueden transplantar o alterarse su crecimiento. Alteraciones "naturales".... La focomelia, como la del malabarista "Le Petit Pepin". Los dedos extra, y la polidactilia simétrica, que duplica las manos. Todo ello producto de alteración de las señales que envían determinados genes.

El sistema de activación de los genes depende a su vez de otros genes, cuestión que plantea un problema teórico, elegantemente (aunque sólo parcialmente) resuelto:

"A primera vista, las jerarquías de este tipo parecen enredarnos en una regresión infinita en la que la carga de producir orden simplemente recae en una serie anterior de entidades que deben, ellas mismas, ser ordenadas. Pero este dilema es más aparente que real. El orden del embrión se crea iterativamente. La precisa presencia del sónico en el ZPA viene definida en parte por la actividad de los genes Hox en el mesodermo del tronco del que brotan las extremidades. Pero el orden geométrico que estos genes dan a la extremidad es tosco; la tarea del sónico es pulirlo. Aparte del sónico hay, por supuesto, otros niveles de refinado en los que el orden se crea a escalas cada vez más pequeñas, y cada una de ellas requiere sutiles e interminables negociaciones, la naturaleza de las cuales apenas comprendemos" (135)

Las extremidades se forman por condensaciones de células que se agregan guiadas por complejas señales que van y vienen, en localizaciones señaladas por los genes Hox que regulan la segmentación del cuerpo. "Muchas de las moléculas que forman las extremidades crean también los genitales, y no debería sorprendernos que algunas mutaciones afecten a ambos" (137)—o sea, que lo de que el pitilín sea el dedito número veintiuno no es tan descabellado como parecía.

V. Carne de mi carne, huesto de mi hueso (De los esqueletos).

En los que hay deformidades como la del chino Arnold y sus descendientes sudafricanos, con falta de huesos en el cráneo y clavículas. El crecimiento de los huesos es controlado por la familia de proteínas BMP. Un transtorno en su inhibición puede dar lugar a la esclerosteosis o a la fibrodisplasia osificante progresiva, como la que sufría Harry Eastlack, invadido de depósitos de huesos. Los experimentos con salamandras de Victor Twitty transplantándoles patas demostraron que los reguladores del crecimiento no están centralizados: "cada pata de salamandra contiene dentro de sí misma la construcción de su propio destino" (153). Otros experimentos más terribles narrados en este capítulo son los del nazi Mengele con las víctimas de Auschwitz: aunque sí sobrevivió a su curiosidad la familia Ovitz, pseudoacondroplásicos que habían formado la "Banda de Jazz de Liliput" y a los que exhibió Mengele con frecuencia. A Mengele nunca se le juzgó ni se le capturó, manda huevos. La pseudoacondroplasia es uno entre varios transtornos causados por mutaciones que inhiben el crecimiento de los huesos. Está la acondroplasia, más frecuente, y la displasia tanatofórica, mortal, resultado de un exceso de la molécula de señalización FG (que regula qué está cerca y qué lejos en el eje de la extremidad del feto). Todo órgano debe poseer señales semejantes que le indiquen cuándo dejar de crecer—y es concebible que haya alteraciones del crecimiento de otros órganos, como músculos extra... aunque estén sin documentar. Otras mutaciones dañan el colágeno de los huesos y dan lugar a osteogénesis imperfecta (como la de Michel Petrucciani). El equilibrio entre crecimiento y destrucción que mantiene el hueso, si se trastoca, da lugar a la conocida osteoporosis o a su contrario, la osteopetrosis, sufrida levemente por Toulouse-Lautrec.

VI. La guerra con las grullas (Del crecimiento).

Los enanos, tan apreciados por los monarcas absolutos—quizá como emblema de sus deseos de superioridad absoluta sobre sus súbditos... Aunque el testimonio del diminuto y longevo Joseph Boruwlaski (ss. XVII-XIX) es optimista, presenta una mirada maravillada ante el mundo "desde abajo". Quizá por un fallo en la hipófisis, siguió creciendo hasta los treinta años, pero sin llegar al metro de altura. A los quince años medía 62 centímetros y medio. En 1782 le presentaron a un gigante en Londres: "mi coronilla apenas alcanzaba la altura de su rodilla". Quizá fuera uno de los dos O'Brien que andaban por londres a fines del XVIII, proclamándose descendientes de Brian Boru. Ninguno se llamaba O'Brien; de uno se sabe que tenía un tumor pituitario.

Hasta bien mediado el XIX no se acreditó la existencia real de los pigmeos, que habían pertenecido a la mitología clásica, con su guerra contra las grullas, desde Homero y Plinio. No se sabe hasta qué edad crecen los pigmeos, pues ellos no saben su edad ni les interesan los calendarios ni cumpleaños. El ritmo humano de crecimiento en la adolescencia es curioso, no se da en otros primates. Al parecer en los pigmeos hay una escasez relativa de la hormona del crecimiento que dse descarga en la adolescencia. Hay otras diversas poblaciones bajitas, por factores que deben combinar la alimentación y la genética. Los negritos, los darus o taron de Brimania—(y más recientemente se ha hablado de los pueblos de pigmeos de la isla de Flores, a cuenta del descubrimiento del hombre de Flores). Es posible que los taron de Birmania sean cretinos—el cretinismo es una alteración neurológica y del crecimiento. Hay una fuerte tendencia al cretinismo en unas poblaciones del norte del congo: el crecimiento y desarrollo sexual se paran a los nueve años—puede que los taron tengan una variedad más suave de lo mismo, sin esterilidad claro. En el Valais suizo también solía haber abundancia de cretinos—por falta de yodo. El bocio es otra afección relacionada—"cuello de Derbyshire" en Inglaterra. Y a esas tribus de hipotéticos cretinos, ¿habría que integrarlos a la modernidad y medicarlos, o respetar su atraso y precario modo de vida?

Crecimiento extra es proporcionado por la castración. Historias de castratos altos, y cantantes célebres, con pechos—y no se quedaban calvos. "El último eunuco de la corte china, Sun Yaoting, no fue enterrado hasta 1996, junto con sus testículos, que habían sido meticulosamente conservados en un tarro" (205). Los eunucos tienden a conservar huesos en estado adolescente—con placas terminales de crecimiento aún activas. "Pero debe haber algo más que detenga el crecimiento aparte del estrógeno" (206). El IGF hace que proliferen las células, pero este crecimiento es regulado entre otros mecanismos por una proteína llamada PTEN. La alteración de este equilibrio entre crecimiento y contención puede dar lugar a alteraciones como el síndrome de Proteo, en el que formaciones óseas crecen descontroladamente—quizá el caso del "Hombre Elefante" James Merrick. Los perros grandes y los niños altos son más susceptibles al cáncer—¿quizá sólo porque tienen más células? O quizá por una descompensación de entrada del IGF—"una hipótesis es que el IGF impide que las células enfermas mueran" (210). Pero por otra parte la estatura en los humanos va asociada a la prosperidad y la salud; las clases altas y pueblos prósperos tienden a ser más altos—de ahí el atractivo omnipresente de la estatura en las figuras públicas. "Pero ¿qué tamaño deberíamos tener?" (215). "Los límites entre lo normal y lo patológico no son sólo borrosos; son móviles, siempre cambiantes, siempre impulsados por la tecnología" (216).

VII. El deseo y la búsqueda de la totalidad (del género).

Nos cuentan la historia de Herculine Barbin, tan cara a Michel Foucault—Herculine, hermafrodita que se crió como mujer, pero al salir, ay, "lesbiana", por así decirlo, le hicieron un cambio de sexo. Cambio sobre el papel (como los que se hacen ahora a voluntad en España), porque sus partes múltiples no se las tocaron. Versa el capítulo sobre la diferenciación sexual, estados intersexuales... y teorías al respecto. Para Vesalio (De humani corporis fabrica, 1543) los órganos sexuales masculino y femenino venían a ser una "inversión" o exteriorización (como un guante reversible, vamos). Esta teoría le llevó a malinterpretar o describir mal lo que veía en sus disecciones.

Otro anatomista de Padua, Renaldo Colombo, "descubrió" (o más bien "describió") el clítoris en 1559. Y hasta 1998 no lo anatomizaron con atención, descubriendo sus raíces y tamaño real. Pero la correspondencia auténtica entre partes masculinas y femeninas se estableció en el XIX: "Las correspondencias ahora quedan claras: pene y clítoris; escroto y labios mayores; uretra y labios menores; y la vagina única para las hembras" (230)—una diferenciación que se hace mediante un "viaje a la masculinidad" a partir de una estructura más bien femenina: "convertirse en hembra es viajar por una autopista recta y ancha" (230). Pero si hay un cromosoma Y, "a la hora de determinar el sexo, como en el tango, el Y manda y el X lo sigue" (231). Así hay varones que tienen más de un cromosoma X, pero al tener un Y, no son varones ambiguos. En concreto es una región del cromosoma Y, la SRY, la que determina el sexo, y varones con cromosoma Y defectuoso pero con esa región intacta siguen siendo varones aunque "de sexo invertido". Y hay hembras XY, "hembras de sexo invertido", que son hembras porque no tienen el SRY donde debía estar. Lo que hace el SRY es controlar las gónadas, y de allí sale la testosterona que altera el ADN para convertir al macho en macho. Si el receptor de la proteína no funciona, lo que iba a ser un macho se convierte en una hembra... sin útero.

Muchos pseudohermafroditas machos no están completamente feminizados al nacer, y tienen genitales ambiguos. Y ha habido frecuentes casos de "cambio de sexo" con el desarrollo de la pubertad...

También en Papúa Nueva Guinea es familiar el caso (más mutantes....: por falta de la enzima 5-alfa-reductasa).

Un exceso de testosterona en la madre puede también masculinizar al feto. Todo esto son mutaciones, pero las mutaciones de identidad sexual suelen dar a esterilidad—callejones sin salida de la evolución... normalmente. El caso de las hienas moteadas es curioso: hay poco dimorfismo sexual, un clítoris que parece un pene, con conducto genitourinario y erecciones... y dan a luz copulan las hembras a traves del clítoris, por carecer de vagina. Una historia dolorosa, en la que lo patológico se ha vuelto normal. Enormes cantidades de testosterona y deficiencia de aromatasa.

Platón narraba en El Banquete un mito sobre el origen del deseo, que tendría un objeto "innato" y no construido, por la divisió nde esos seres esféricos dobles de sexo diferente o igual. La antropología del siglo XX (Boas, Margaret Mead) enfatizó el constructivismo sexual, pero "dichas ideas constructivistas del género están perdiendo fundamento rápidamente ante el estudios genético molecular del comportamiento sexual" (243).

VIII. Una frágil burbuja (de la piel).

Nos llamamos homo sapiens desde 1758 gracias a Linneo (Systema Naturae, 10ª ed.). Estuvo a punto de llamarnos homo diurnus, porque creía en la existencia de los míticos trogloditas, ahora exiguos supervivientes de una antigua raza numerosa—ellos serían el homo nocturnus; "Linneo injertó en su imagen una antigua tradición que hablaba de una raza remota y oculta de gentes antinaturalmente blancas, de ojos dorados, e intensamente fotofóbicas" (250). Tomó Linneo el grabado de la humanizada "orangutana" blanca de Jacob Bontius (Historia naturalis indiae orientalis, 1658) y lo rebautizó Homo troglodytes. (Sería interesante seguir la pista a estas leyendas de trogloditas fotofóbicos tras el descubrimiento del Hombre de Flores, y las leyendas en torno al Ebu gogo... ¿quizá aún no extintos en tiempos de Linneo, al menos en la memoria? Quién sabe. Es interesante en todo caso esta vieja edición del ensayo de Tyson sobre los pigmeos. De los trogloditas de Linneo también habla Huxley en "The Man-Like Apes"). A Leroi le parece que Linneo estaba pensando en albinos al hablar de estos trogloditas—aunque claro se mezclan más historias en la mente de Linneo.

Buffon también se interesó por los albinos, habla de la negra albina Geneviève, blanca como la tiza, en su Histoire Naturelle—"Buffon le midió las extremidades, la cabeza, los pies, el pelo: dedica todo un párrafo a sus pechos, observa que era virgen, y luego, con interés, que era capaz de ruborizarse" (252). Había mucho albinismo al parecer entre los negros del caribe. (Y últimamente llegan muchas noticias de los albinos perseguidos en algunos países africanos: al parecer muchas malas bestias ignorantes los quieren para matarlos ritualmente y bebérseles la sangre—que suponen les dará no sé qué beneficios vitales). Los picazos son un caso también frecuente en el Caribe (piel a corros o manchas, albina y negra). Los melanocitos, células que dan color a la piel, derivan de las mismas células de la cresta neural que forman la cara—algunas se desplazan y dan lugar a nervios, músculos, glándulas, y a los pigmentos de la piel. "La piel picaza es causada por mutaciones en, al menos, cinco genes distintos, y cada una de ellas desactiva uno o más dispositivos de ésos" (259)—y en los casos graves hay complicaciones variadas, intestinales, o sordera, por conexiones genéticas en la formación de todos estos sistemas.

Hay varios genes que determinan el color de la piel. Y es un tema delicado por su asociación a la concepción que se tiene de la raza. En Sudáfrica, con las leyes raciales, había cierta vaguedad en la cuestión: que fueses "de color" dependía tanto de tu círculo social que del tono exacto de la piel. Pero a pesar de eso una ciudadana "blanca", Rita Hoefling, tuvo problemas al volverse negra espontáneamente.... y luego se convirtió en blanca de nuevo. Sufría del síndrome de Nelson, frecuente tras la extirpación de la glandula suprarrenal. Un exceso de hormona pituitaria, controlada por esa glándula, hizo oscurecerse su piel. La falta de melanotropinas, por el contrario, va asociada a pelo pelirrojo y gordura: la misma molécula tiene efectos distintos en distintas partes del cuerpo, y en este caso va asociada también a la señal neuronal que nos ordena dejar de comer cuando estamos saciados.

Pero la mayoría de los pelirrojos, no gordos, se deben a otra cuestión: unos receptores inactivos en sus melanocitos: la actividad les haría fabricar eumelanina, pigmentos marrones; la inactividad da lugar a fabricación de feomelanina (pigmentos rojos):

"Los celtas pelirrojos poseen receptores que están inactivos de manera más o menos permanente, algo que comparten con los setters rojos, los zorros rojos y el ganado de las Highlands de pelo rojo" (265)

¿Pero por qué llamar a los pelirrojos mutantes, en lugar de considerarlos un polimorfismo? "las mutaciones son raras y perjudiciales, los polimorfismos no suelen ser ni una cosa ni otra" (265). Globalmente considerados, los pelirrojos son raros; la mutación podría ser adaptativa en los climas con poco sol del norte, o al menos no ser dañina allí, con lo cual el gen del pigmento entra en desuso, pero es muy dañina en los trópicos.

Los chinos estaban extrañados por la pilosidad de los europeos y los aínos. Y las pilosidades excepcionales han atraído siempre la atención. Petrus Gonsalvus, de las Canarias, vivó en varias cortes europeas en el siglo XVI; sufría de hiperetricosis lanuginosa, y varios de sus hijos (retratados con frecuencia, como él) fueron también peludos. El cuadro que pintó Lavinia Fontana de la hija de Petrus, Tognina, ilustra la portada del libro de Leroi, y este artículo. El viajero John Crawfurd describe a otra familia extraordinariamente velluda en Birmania. Estos acabarían viajando a Europa para exhibirse como curiosidades.

Después de una sección sobre calvicie y pilosidad, Leroi señala el parentesco embriológico entre pelos, dientes y pechos:

"Todos ellos son lugares en los que la piel se ha hinchado o ha formado una cavidad para producir algo nuevo. El simple tubo que es un folículo piloso, el robusto yunque de dentina y esmalte que es un diente y la abultada carga de conductos que es un pecho, son todo variaciones sobre un tema constructivo. Un trastorno genético—hay más de cien—que afecte a uno de esos órganos a menudo afectará a otro.

Esos órganos no sólo comparten el hecho de que se originan en la piel; también se construyen más o menos del mismo modo. A medida que los folículos pilosos se forman por toda la epidermis del feto, otras células epidérmicas se aglutinan y forman cavidades para producir dientes o glándulas mamarias. Al igual que el folículo piloso, cada uno de estos órganos de la piel es una quimera, parte ectodermo, parte mesodermo". (283-84).

Entre las alteraciones son frecuentes los pechos o pezones extra—en los europeos, normalmente debajo de los normales, en los japoneses por encima o en las axilas. Linneo creó la clase de los mamíferos en base a la presencia de pechos. Al Homo sapiens no lo describe, sino que sólo le atribuye la capacidad de conocerse a sí mismo. Es curioso que la diosa de la Razón en su frontispicio era Artemisa, con cuatro pechos.

IX. La vida sobria (Del envejecimiento).

CONTINUARÁ....

martes, 25 de septiembre de 2018

Las mentiras de la Notaria Mayor del Reino

PSOE y sus socios separratas, contra el español

🏛 Sánchez y sus socios separatistas y populistas tumban nuestra ley para acabar con las barreras lingüísticas en el empleo público. El sanchismo impide la igualdad entre españoles que hoy ha defendido brillantemente @Tonicanto1. pic.twitter.com/BlT8CiQoPt— Albert Rivera (@Albert_Rivera) 25 de septiembre de 2018

Federico a las 6: La Ley de Cs contra la discriminación lingüística.

Un imbécil llamado Zapatero

Después del discurso de hoy de Trump en la ONU, Zapatero y los demás colaboratas de Maduro lo tienen claro. Les van a dar pal pelo en la escena internacional.

El diplomático delicado: https://www.libertaddigital.com/opinion/emilio-campmany/el-diplomatico-delicado-86101/

The Arthurian Legend

(From George Sampson's Concise Cambridge History of English

Literature, 3rd ed.).

XII. THE ARTHURIAN LEGEND

The mystery of Arthur's end is not darker than the mystery of his

beginning. While the ancient tradition is everywhere, the facts and

records are nowhere. The earliest English Arthurian literature is

singularly meagre and undistinguished. The romantic exploitation of

"the matter of Britain" was the achievement, mainly, of French writers,

and, indeed, some critics would have us attach little importance to

British influence on the development of the Arthurian legend. The

"matter of Britain" very quickly became international property—a vast

composite body of romantic tradition, which European poets and

story-tellers of every nationality drew upon and used for their own

purposes. Arthur was non-political and could be idealised without

offence to any ruling family. The British king himself faded more and

more into the background, and became, in time, but the phantom monarch

of a featureless "land of faëry". His knights quite overshadow him in

the later romances; but they, in their turn, undergo the same process

of denationalization, and appear as natives of some region of fantasy,

moving about in a golden atmosphere of illusion. The course of the

story is too obscure to be made clear in a brief summary which must

necessarily ignore the hints and half-tones that count for much in the

total effect, and which can take no account of French, German and

Italian contributions to the legend. Old English literature, even the Chronicle,

knows nothing whatever of Arthur. To find any mention of him earlier

than the twelfth century we must turn to Wales, where, in a few obscure

poems, a difficult prose story, and two dry Latin chronicles we find

what appear to be the first written references, meagre and casual, but

indicating a tradition already ancient. The earliest is in Historia

Britonum, which, as we have seen (p. 9), dates from 679, though the

existing recension of Nennius was made in the ninth century. The

reference of Nennius to Arthur occurs in a very short account of the

conflict that culminated in Mount Badon, usually dated 516, though some

would put it as early as 470. Gildas, who was a youth in 516, also

mentions Mount Badon; but the only hero he names is "Ambrosius

Aurelianus". In Nennius the hero has become "The magnanimous Arthur",

who was twelve times victorious, last of all at Mount Badon; but he is

a military leader, not a king—or, perhaps, as the anthropologist Lord

Raglan thinks, "a god of war".

The poems of the ancient Welsh bards have been discussed almost as

fiercely as the poems of Ossian; yet there is no doubt that together

with much of late and doubtful invention they contain something of

indisputably ancient tradition. But the most celebrated of the early

Welsh bards know nothing of Arthur. Llywarch Hên, Taliesin and Aneirin

(sixth or seventh century?) never mention him; to the first to Urien,

Lord of Rheged, is the most imposing figure among all the native

warriors. There are, indeed, only five ancient poems that mention

Arthur at all. The reference most significant to modern readers occurs

in the Stanzas of the Graves contained in the Black Book of

Caermarthen (twelfth century): "A grave there is for March (Mark),

a grave for Gwythur, a grave for Gwgawn of the Ruddy Sword; a mystery

is the grave of Arthur." Another stanza mentions both the fatal battle

of Camlan and Bedwyr (Bedivere) , who shares with Kai (Kay)

pre-eminence among Arthur's followers in the primitive Welsh fragments

of Arthurian fable. Another Arthurian knight, Geraint, is the hero of a

poem that appears both in The Black Book of Caermarthen and in

the Red Book of Hergest (fourteenth century). One of the

eighteen stanzas just mentions Arthur by name. The Chair of the

Sovereign in The Book of Taliesin (thirteenth century)

alludes obscurely to Arthur as a "Warrior sprung from two sources".

Arthur, Kai and Bedwyr appear in another poem contained in The

Black Book; but the deed celebrated in the almost incomprehensible

lines of this poem are the deeds of Kai and Bedwyr. Arthur recedes

still further into the twilight of myth in the only other Old Welsh

poem where any extended allusion is made to him, a most obscure piece of

sixty lines contained in The Book of Taliesin. Here, as Matthew

Arnold says, "The writer is pillaging an antiquity of which he does not

fully possess the secret". Arthur sets upon various expeditions over

perilous seas in his ship Pridwen; one of them has as its object the

rape of a cauldron belonging to the King of Hades. Ancient British

poetry has nothing futher to tell us of this mysterious being, who is,

even at a time so remote, a vague, impalpable figure of legend.

The most remarkable fragment of the existing early Welsh literature

about Arthur is the prose romance of Kulhwch and Olwen,

assigned by most authorities to the tenth century. It is one of the

stories that Lady Charlotte Guest translated from the Red Book of

Hergest and published in The Mabinogion (1838). Of the

twelve "Mabinogion", or stories for the young (the word has a

special meaning but is loosely used), five deal with Arthurian themes.

Two, Kullwch and Olwen and The Dream of Rhonabury, are

British; the other three are based on French originals. In The

Dream of Rhonabury, Arthur and Kai apper, Mount Badon is mentioned,

and the fatal battle of Camlan with Mordred is referred to in some

detail. The Arthuro Kullwch and Olwen bears little resemblance

to the mystic king of later legend, except in the magnitude of his

warrior retinue, in which Kai and Bedwyr are leaders. Arthur, with his

dog Cavall, joins in the hunt for the boar Twrch Trwyth through

Ireland, Wales and Cornwall, and his many adventures are clearly relics

of ancient wonder-tales of bird and beast, wind and water. The wild and

even monstrous Arthur of this legend is equally remote from Nennis and

from Malory; but the charm of the story is someething that the

long-winded Continental writers could not achieve.

The serious historian William of Malmesbury, who wrote a few years

earlier than Geoffrey of Monmouth, refers to Arthur as a hero worthy to

be celebrated in authentic history and not in idle fictions. He adds,

"The sepulchre of Arthur is nowhere to be seen, whence ancient ballads

fable that he is to come." Plainly, Arthur was already a popular

tradition. The transformation of the British Arthru into a romantic

hero of European renown was the result of contact between British and

Norman culture. No doubt the Normans got their first knowledge of

Arthurian story from Brittany; but the real contact was made in Britain

itself, where the Normans had succeeded in establishing intimate

relations with the Welsh. Thus the true father of the Arthurian legend

is Geoffrey of Monmouth. How much he derived from ancient sources we

shall probably never find out; but we can reasonably assume that he did

not invent the fabric of the story, however fancifully he embroidered

it. And, after all, the real point is not how much he invented, but how

he used his matter, historical or legendary. Geoffrey had the art of

making the improbable seem probable, and his ingenious blending of fact

and fable not only gave his book a great success with readers, but made

Arthur and Merlin the romantic property of literary Europe. So it has

been urged thet we shoul take Geoffrey's compilation, not as a national

history, but as a national epic, doing for Britain what the Aeneid

did for Rome, and finding in the mythical Brutus, great-grandson of

Aeneas, the name-giving founder of the British state. In such a story

all the legends have their natural place. Geoffrey's History is

thus the first Brut—for so in time the records of early British

kings with this mythical starting-point came to be called. The first

few books of Historia Regum Britanniae relate the deeds of

Arthur's predecessors. At the close of the sixth book the weird figure

of Merlin appears on the scene, and romance begins to usurp the place

of sober history. Arthur is Geoffrey's hero. He knows nothing of

Tristam, Lancelot or the Holy Grail; but it was he who, in the Mordred

and Guenevere episode, first sugggested the love-tragedy that was to

become one of the world's imperishable romances.

In the Latin Life of Gildas written at about the time of

Geoffrey's death there is a further interesting allusion. Arthur is

described as being engaged in deadly feud with the King of Scotland,

whom he finally kills; he subsequently comes into collision with

Melwas, the wicked king of the "summer country" or Somerset, who had,

unknown to him, abducted his wife Guenevere, and concealed her in the

abbey of Glastonia. This seems to be the earliest appearance o the

tradition which made Melwas (the Mellyagraunce of Malory) an abductor

of Guenevere. Some of the Welsh traditions are used in Peacock's

delightful story The Misfortunes of Elphin, Melwas and the

abduction both appearing.

The value of the Arthurian story as matter for verse was first

perceived in France; and the earliest surviving standard example of

metrical narrative or romance derived directly or indirectly from

Geoffrey is Li Romans de Brut by Wace, who, born in Jersey,

lived at Caen and Bayeux, and completed his poem in 1155. Some of the

matter is independent of Geoffrey's History. Thus, it is Wace,

not Geoffrey, who first tells of the Round Table. The poem, 15,000

lines long, written in lightly rhyming verse and in a familiar

language, was very popular. Wace's Brut, possibly in some form

not now existing, or in some blend with other chronicles, provided the

foundation of Layamon's Brut, the only English contrubution of

any importance to Arthurian literature before the fourteenth century;

for, so far, all the matter discussed is in Welsh or Latin or French.

Layamon added something personal to the essntially English character of

his style and matter, and he gives us as well details not to be found

in Wace or Geoffrey. Thus, he amplifies the story of the Round Table

and narrates the dream of Arthur, not to be found in Geoffrey or Wace,

which foreshadows the treachery of Mordred and Guenevere, and disturbs

the king with a sense of impending doom. Layamon's enormous and uncouth

epic has the unique distinction of being the first celebration of "the

matter of Britain" in the English tongue.

Not the least remarkable fact about the story of King Arthur is its

rapid development as the centre of many gravitating stories, at first

quite independent, but now permanently part of the great Arthurian

system. Thus we have the stories of Merlin, of Gawain, of Lancelot, of

Tristram, of Perceval, and of the Grail. A full account of these

associated legends belongs to the history of French and German, rather

than of English, literature, and is thus outside our scope. In origin

Merlin may have been a Welsh wizard-bard, but he makes his first

appearance in Geoffrey and quickly passes into French romance, from

which he is transferred to English story. Gawain is the hero of more

episodic romances than any other British knight; when he passes into

French story he begins to assume his Malorian (and Tennysonian)

lightness of character. He is the hero of the finest of all Middle

English metrical romances, Sir Gawayne and the Grene Knight,

and, as Gwalchmai, he plays a large part in the story called Peredur

the Son of Evrawc, included in the Mabinogion. Peredur is

Perceval, and the story comes from French romance. The love of Lancelot

for Guenevere is now a central episode of the Arthurian tragedy, but

Lancelot is actually a late-comer into the legend, and his story is

told in French. The book to which Chaucer refers in The Nun's

Priest's Tale and Dante in the famous passage of Inferno VI

is perhaps the great prose Lancelot traditionally attributed to

Walter Map (see p. 21). The Grail story is another complicated addition

to the Arthurian cycle. Out of the quest for various talismans, no

doubt a part of Celtic tradition, developed the story of Perceval, as

told in French and German romances; and the "Grail", a primitive

symbol, proved capable of semi-mystical religious interpretation, and

came to be identified with the cup of the Last Supper in which Joseph

of Arimathea treasured the blood that flowed from the wounds of the

Redeemer. The story of Tristram and Iseult is probably the oldest of

the subsidiary Arthurian legends, and we find the richest versions in

fragments of French poems and fuller German compositions. The English

literature of Tristram is very meagre. The whole story bears every mark

of remote pagan and Celtic origin. Finally, as an example of how

independent legends were caught into the great Arthurian system, let us

note the Celtic fairy tale of Lanval, best known in the lay of

Marie de France (c. 1175), a fascinatingly obscure personality

who, possibly English, wrote in French. And as a postcript we may note

that the sceptical twentieth century has nevertheless not lagged behind

the Middle Ages or the Victorians in its devotion to King Arthur, as

witness the Arthurian trilogy Merlin, Lancelot and Tristram

(1917-27) by the American poet Edwin Arlington Robinson, the reshaping

of the Grail legend in John Cowper Powys's Glastonbury Romance

(1933), Charles Williams's Taliessin through Logres (1938) and The

Reign of the Summer Stars (1944), and T. H. White's

trilogy The Once and Future

King (1958), which inspired the American stage and film success Camelot.

Through all the various strains of Arthurian story we hear "the horns of Elfland faintly blowing"; and it is quite possible that, to the Celtic wonderland, with its fables of the "little people", we owe much of the fairy-lore which has, thorugh Shakespeare and poets of lower degree, enriched the literature of England. Chaucer, at any rate, seemed to have no doubt about it, for he links all that he knew, or cared to know, about the Arthurian stories with his recollections of the Fairy world:

In th' oldë dayës of the King Arthoúr,So let us believe with the poets, and leave the British Arthur in his unquestioned place as the supreme king of Romance.

Of which that Britons speken greet honóur,

Al was this land fulfild of fayerye;

The elf-queen with hir joy companye

Dauncëd ful ofte in many a greneë mede.

The Celts: From Camelot to Christ: